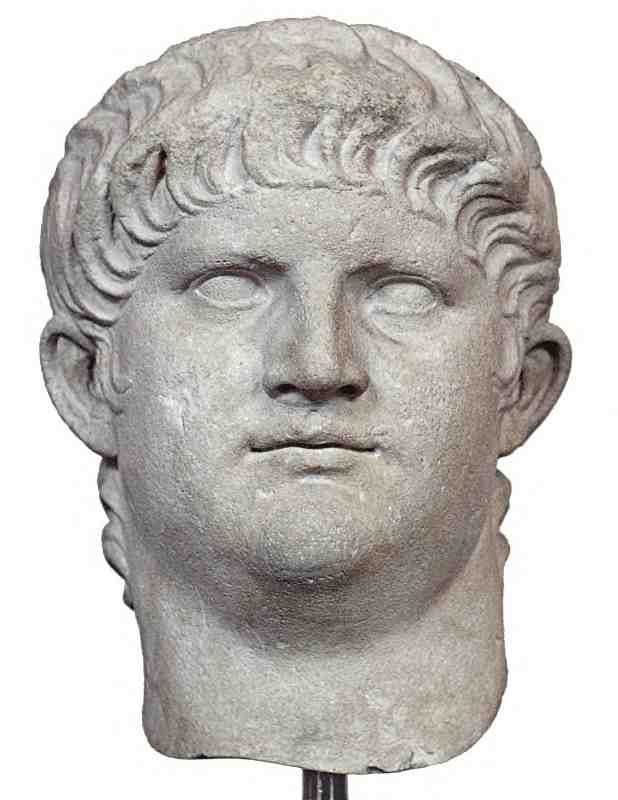

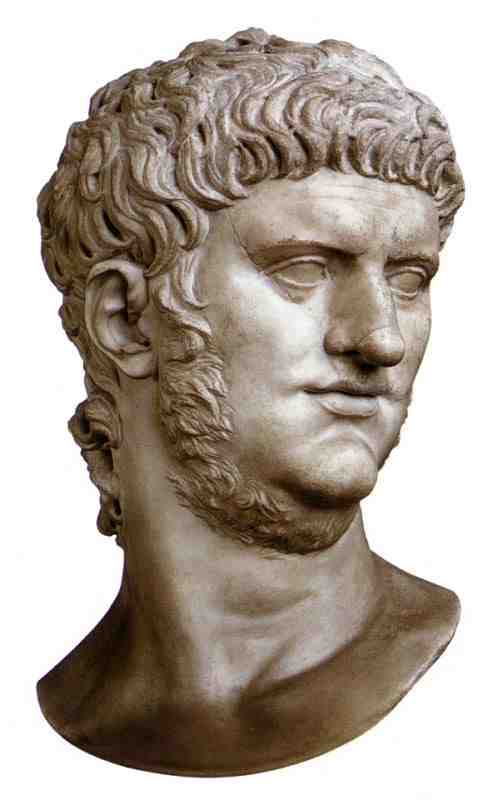

Nero (Reign: AD 54 to 68)

The following is a chapter from a soon to be published book, In the Days of These Kings: The Prophecy of Daniel in Preterist Perspective.

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was the grand-nephew of Claudius Caesar. Nero’s father, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, died when he was young. He became his great uncle’s heir due to the incestuous marriage of Claudius to his mother, Agrippina, the emperor’s niece and fourth wife.

The consensus of ancient historians is that Agrippina murdered Claudius by poison contained in a plate of mushrooms. Agrippina had manipulated Claudius to name her son Nero as his heir. When Claudius admitted that had been a mistake, she had her husband poisoned before Claudius’ son, Britannicus, could come of age.

Upon the death of Claudius, Nero became the youngest emperor of Rome thus far at the age of 17. In the beginning of his reign, Nero relied on the guidance of his mother, but soon tired of her domineering and manipulative personality. Nero listened to his advisers, Seneca and Burrus, who were competent, but over time they gradually lost their influence.

Once severed from her influence over her son, Agrippina began pushing for Britannicus, Nero’s younger step-brother and uncle, to be reinstated as the true heir to Claudius. Nero responded by having the 14-year-old boy poisoned. Nero then set about cutting off the influence of his experienced advisers by falsely accusing them of crimes, such as treason, conspiracy and embezzlement, from which they were eventually acquitted by the Senate.

In the beginning of his reign, Nero was popular with the lower classes. He reformed the laws of Rome and initiated many building projects. Under his advisors’ influence, Nero ruled with moderation, reduced taxes, gave slaves the right to file complaints against their owners and pardoned prisoners arrested for sedition. He often appeared at the games, drove a chariot in races, sang and performed readings of his poetry publicly – often for many hours before a captive audience. Suetonius portrays Nero as neglecting his governing duties for months at a time in order to play in the Olympic Games in which he once emerged as the victor even when he failed to finish a chariot race. Suetonius’ account of Nero’s conceits is often comical.

He ordered those contests which normally took place only at long intervals to be held during his visit, even if it meant repeating them; and broke tradition at Olympia by introducing a musical competition into the athletic games…. No one was allowed to leave the theatre during his recitals, however pressing the reason, and the gates were kept barred. We read of women in the audience giving birth, and of men being so bored with the music and the applause that they furtively dropped down from the wall at the rear, or shammed dead and were carried away for burial (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 23, Robert Graves translation).

Nero did not come to power with an impressive military resume like the five Caesars before him. Instead he wanted to be known as an artist, actor, poet and athlete. His behavior was always eccentric and erratic, but he became increasingly paranoid, perverse and psychotic as he grew into adulthood.

It is difficult to limit the amount of information showing that Nero is the fulfillment of both Daniel’s prophecy and the corresponding passages in John’s Revelation. An entire book would be necessary just to contain the amount of reference material showing how closely Nero fits the description of the “little horn” of Daniel 9 and the Beast from Sea, the man with the number of 666, described in Revelation 13 and 17. I will give a historical outline and some references here.

Who was Poppaea Sabina?

A little known footnote of history is that Nero married an older woman named Poppaea Sabina who is thought to have been a Jewish proselyte. Tacitus called her mother, Poppaea Sabina the Elder, “the loveliest woman of her day.” Poppaea evidently shared her mother’s great beauty. Tacitus also painted her as being scheming and ambitious. She had been married to Rufrius Crispinus when she was 14-years-old. Ancient historians claim she married her second husband, the later Emperor Otho, who was a best friend of Nero, in order to get close to the throne. She then seduced Nero with her beauty.

In AD 58, Poppaea became Nero’s mistress while he was married to his first wife, Octavia. Nero’s mother, Agrippina, opposed his marriage to Poppaea, seeing her to be an ambitious woman. Sometime later, Nero began to plot to murder his own mother. Tacitus states that Poppaea induced Nero to murder Agrippina in AD 59 so that she could marry him.

The murder was contrived at first to look like an accident in which his mother was crossing a bay along the coast on barge. The boat was set to sink so that she would drown. When Agrippina swam to shore, Nero became frustrated. He had his mother killed by framing her in a botched plot to assassinate him with the aid of a freed slave named Agermus. Nero then claimed his mother committed suicide as a result of the conspiracy being foiled.

For want of a better plan, Nero ordered one of his men to drop a dagger surreptitiously beside Agermus, whom he arrested at once on a charge of attempted murder. After this he arranged for Agrippina to be killed, and made it seem as if she had sent Agermus to assassinate him, but committed suicide on hearing that the plot had miscarried. Other more gruesome details are supplied by reliable authorities: it appears that Nero rushed off to examine Agrippina’s corpse, handling her legs and arms critically and, between drinks, discussing their good and bad points. Though encouraged by the congratulations which poured in from the Army, the Senate and the people, he was never thereafter able to free his conscience from the guilt of this crime. He often admitted that the Furies were pursuing him with whips and burning torches; and set Persian mages at work to conjure up the ghost and make her stop haunting him (Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 34).

Seneca wrote a dishonest defense to the Senate explaining the reasons for Agrippina’s death and exonerating Nero of the murder. Poppaea then grew jealous of everyone around Nero, including his wife Octavia and his advisers, Seneca and Burrus, and pushed for their removal. Nero did not formally marry Poppaea until his divorce from his first wife Octavia in AD 62. Octavia had not given Nero an heir and the two became estranged. After Nero divorced Octavia citing her infertility, he accused her of adultery and had her killed.

According to Josephus, Poppaea had a more noble character than that of the scheming woman described by Tacitus and Suetonius. Josephus twice uses a Greek word to describe her, theosebeis, which is translated as, “God-fearer,” God-worshipper,” or “religious woman.” This probably means she was either a Jew, a proselyte to Judaism or at least was a sympathetic advocate to the Jews among her friends. The Jews had been expelled from Rome by the decree of Claudius in AD 49, but Nero allowed them to return when he became emperor. Poppaea became the Jews’ strongest advocate in Rome. Josephus describes two cases in which Poppaea influenced Nero in his dealings with the Jews.

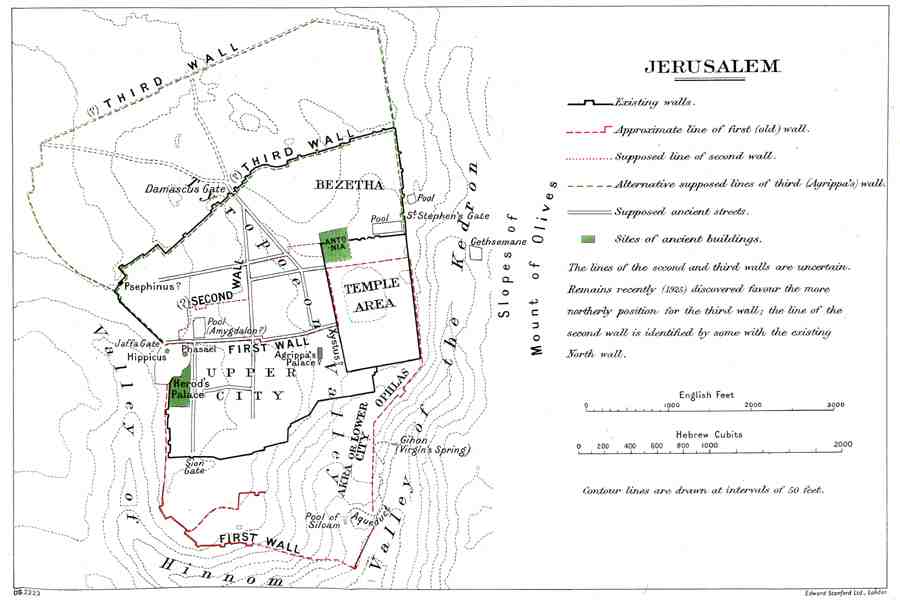

The first is an event that took place around AD 59, shortly after Festus became the procurator of Judea. King Herod Agrippa II had built an elevated dining room in his palace in Jerusalem from which he could observe the courts of the Temple. The priests considered this a sacrilege and built a wall facing the west to block Agrippa’s view.

At these doings both king Agrippa, and principally Festus the procurator, were much displeased; and Festus ordered them to pull the wall down again: but the Jews petitioned him to give them leave to send an embassage about this matter to Nero; for they said they could not endure to live if any part of the temple should be demolished; and when Festus had given them leave so to do, they sent ten of their principal men to Nero, as also Ismael the high priest, and Helcias, the keeper of the sacred treasure. And when Nero had heard what they had to say, he not only forgave them what they had already done, but also gave them leave to let the wall they had built stand. This was granted them in order to gratify Poppaea, Nero’s wife, who was a religious woman, and had requested these favors of Nero, and who gave order to the ten ambassadors to go their way home; but retained Helcias and Ismael as hostages with herself. As soon as the king heard this news, he gave the high priesthood to Joseph, who was called Cabi, the son of Simon, formerly high priest (Josephus, Antiquities XX.8.11).

The fact that Nero kept the high priest and the temple treasurer as “hostages” has been interpreted by Judaic scholar, Louis Feldman, to mean he kept them as expert teachers of the Jewish religion to please Poppaea.

The second event took place around AD 63, when Josephus actually met Poppaea in the flesh. Josephus had come to Rome to plead for the release of some Jewish priests in Jerusalem who had been sent as prisoners by the procurator Felix several years before to appear before Nero in Rome on trumped up charges. Through the friendship of a Jewish comedian actor named Aliturus, a favorite of Nero, Josephus was introduced to Poppaea.

I was introduced to Poppaea, Caesar’s wife, and I took the earliest opportunity to ask her to free the priests. Having received large gifts from Poppaea in addition to this favor, I returned to my own country (Josephus, The Life of Flavius Josephus, III.2).

What were the circumstances of Apostle Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome?

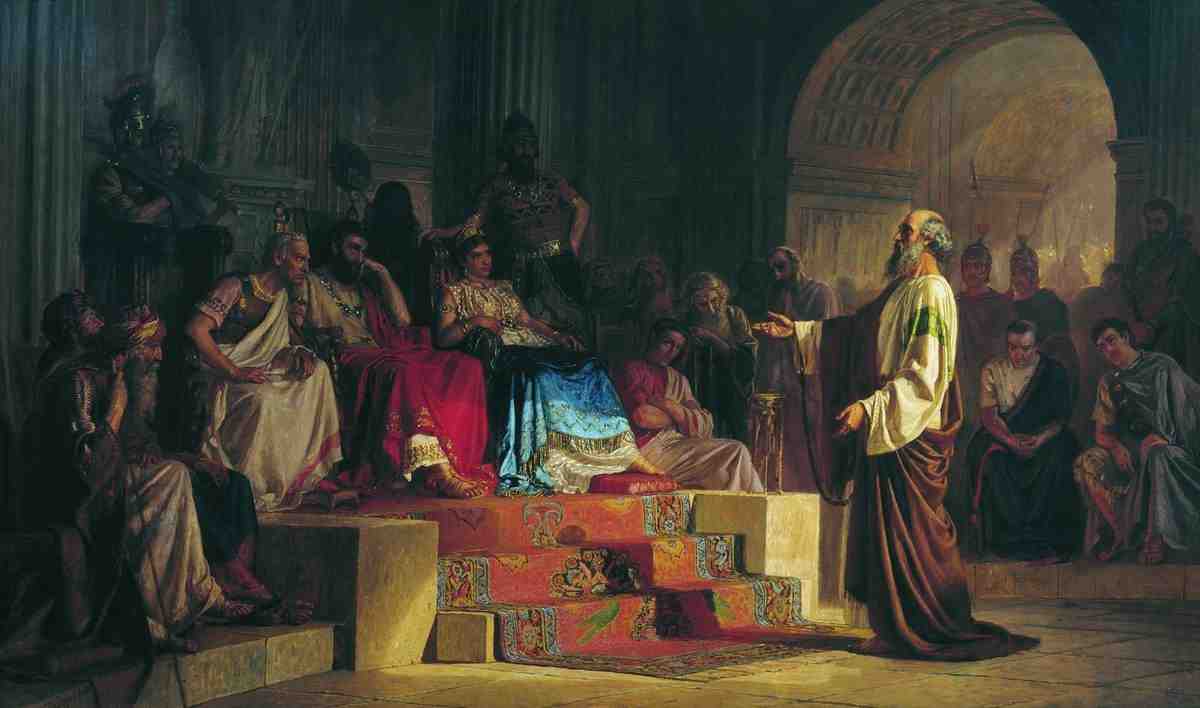

It was into this royal household of sexual and political intrigue that the Apostle Paul appeared as a captive at Rome. Paul had been the center of a controversy over his preaching of the Gospel with the Jews in Jerusalem. He had been forewarned by the prophet Agabus that he would be bound by the Jews and delivered into the hands of the Gentiles (Acts 21:10,11). The Jews used a false charge of sedition in order to hatch a plot to have Paul murdered as he was being delivered to a council of chief priests and elders. However, Paul knew by revelation that he was to stand before Nero Caesar himself as a witness for the Gospel.

But the following night the Lord stood by him and said, “Be of good cheer, Paul; for as you have testified for Me in Jerusalem, so you must also bear witness at Rome” (Acts 23:11).

As a Roman citizen accused of sedition, he had the right to appeal to Caesar, although the extradition to Rome and the wait for trial would take several years. He appealed first to the Roman procurator Felix at Caesarea, who seemed genuinely interested in hearing more about “the Way” Paul was preaching. Felix found no fault in Paul, but held him for two years until he was replaced by Festus. When Festus heard Paul preach, he wanted to curry favor with the Jews by turning him back over to the council. But Paul maintained his innocence and insisted that his case be heard before Caesar.

Here Paul played his trump card. The law of appeal to Caesar was sacred to the Romans. Under Julian law any magistrate, or any other with Roman authority, who put to death or tortured a Roman citizen who had made an appeal to Caesar, could be condemned themselves with a death sentence. This appeal was generally used as a last defense. Most citizens would not want to appear before the emperor of Rome. But Paul had to go to Rome according to the word of prophecy. This also relieved Festus of his obligation to the Jews, which is what he wanted.

By chance, King Herod Agrippa II of Judea came to visit Festus to pay his respects. Since Agrippa was a Jew, Festus began to tell him about Paul and his testimony of Jesus who was seen alive after being crucified. Festus arranged to have Paul make his case before Agrippa and his sister Berenice. The next day, Agrippa gave Paul the right to speak freely. Agrippa came under conviction and declared that Paul was innocent.

And Agrippa said to Festus, “This man might have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar” (Acts 26:32).

Nero was the “Caesar” referred to when Apostle Paul made his appeal.

“I stand at Caesar’s judgment seat, where I ought to be judged … I appeal to Caesar” (Acts 24:10,11).

Throughout the narrative, Nero is also called “Augustus,” which was the family name and later throne name of all the Caesars.

What was “Caesar’s household”?

Nero was also the emperor referred to when Paul wrote the closing greetings to his Epistle to the Church at Philippi.

All the saints greet you, but especially those who are of Caesar’s household (Philippians 4:2).

Paul wrote these words from Rome near the end of his first imprisonment around AD 62. This closing greeting, together the account of Acts 28 and the lengthier closing greeting in Romans 16 gives us more information on the progress of the Gospel in the city of Rome.

“Caesar’s household” was all the slaves and freemen alike, living in and near the palace of the emperor on Palatine Hill at Rome. This was a vast number of people, easily hundreds if not thousands, since Nero was constantly engaged in building projects in and around the palace. Many of the slaves of city of Rome were Jews and many of them would have been in employed on the palace grounds.

We are not told how many disciples Paul made while he was in Rome. Luke wrote only that as a prisoner Paul was under what would be considered “house arrest” and free to preach the Gospel to everyone he encountered. In fact, Acts 28 notes that they found believers when they first arrived in Italy.

And landing at Syracuse, we stayed three days. From there we circled round and reached Rhegium. And after one day the south wind blew; and the next day we came to Puteoli, where we found brethren, and were invited to stay with them seven days. And so we went toward Rome. And from there, when the brethren heard about us, they came to meet us as far as Appii Forum and Three Inns. When Paul saw them, he thanked God and took courage. Now when we came to Rome, the centurion delivered the prisoners to the captain of the guard; but Paul was permitted to dwell by himself with the soldier who guarded him (Acts 28:12-16).

The narrative then concerns some Jews living in Rome who came to hear Paul preach the Gospel.

Then they said to him, “We neither received letters from Judea concerning you, nor have any of the brethren who came reported or spoken any evil of you. But we desire to hear from you what you think; for concerning this sect, we know that it is spoken against everywhere.”

So when they had appointed him a day, many came to him at his lodging, to whom he explained and solemnly testified of the kingdom of God, persuading them concerning Jesus from both the Law of Moses and the Prophets, from morning till evening. And some were persuaded by the things which were spoken, and some disbelieved. (Acts 28:21-24).

Paul then preached words from Isaiah 6:9,10 condemning those who would not believe and resolving that the Gospel was destined to be preached instead to the Gentiles.

Then Paul dwelt two whole years in his own rented house, and received all who came to him, preaching the kingdom of God and teaching the things which concern the Lord Jesus Christ with all confidence, no one forbidding him (Acts 28:30,31).

In Philippians, which was written during Paul’s first imprisonment at Rome, Paul corroborates that he was able to preach the Gospel in Nero’s palace.

But I want you to know, brethren, that the things which happened to me have actually turned out for the furtherance of the gospel, so that it has become evident to the whole palace guard, and to all the rest, that my chains are in Christ; and most of the brethren in the Lord, having become confident by my chains, are much more bold to speak the word without fear (Philippians 1:12-14).

The eminent Bible commentator, J.B. Lightfoot, did an intriguing dissertation as part of his commentary on Philippians on what was meant by “Caesar’s household” (Philippians 4:2).

Some of Lightfoot’s suggestions and conjectures on this subject are exceedingly interesting. He reviews the names of the persons to whom Paul sends greeting in Romans 16 and compares them with the names of persons who lived at that time, and which have been found in monumental inscriptions on the columbaria or places of sepulture exhumed on the Appian Way. Many of the occupants of those columbaria were freedmen or slaves of the emperors, and were contemporaries of Paul. The result of Lightfoot’s review of the names is that he claims to have established a fair presumption that among the salutations in Romans some members at least of the imperial household are included.

In the household of the emperor there were necessarily many persons of high rank. Perhaps we may find a hint that the gospel had been embraced by some in the higher grades of society, in such strange facts as the execution of Titus Flavius Clemens, a man of consular rank and cousin to the emperor, and also in the fact that Flavia Domitilla, the wife of Flavius Clemens, was banished by Domitian, notwithstanding her near relationship to him, for she was the emperor’s niece. Her daughter Portia also shared in the same punishment of exile. The charges brought against all three were atheism and inclination to Jewish customs: surely such charges were sufficiently vague and even self-contradictory. The opinion has been suggested that probably these three persons in the inner circle of the emperor’s kinsmen were Christians (“Caesar’s Household,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia).

In fact, the “Clement” that Paul mentions in Philippians 4:3, “my fellow laborer” in Christ, is thought by some to be Clement of Rome. Clement was the writer of an Epistle to the Corinthians in about AD 96 that first recorded the martyrdom of Peter and Paul. J.B. Lightfoot wrote an additional dissertation in his commentary discussing evidence for this possibility. Some have suggested that Clement was a slave or a freedman of a member of the royal family, Titus Flavius Clemens, whom the Emperor Domitian had executed for having sympathy for “Jewish customs.” During this time, the common charge against both Jews and Christians was “atheism” since according to the Roman worldview they denied the Roman gods.

Why does the account of Acts 28 stop at this point?

After stating that Paul had free reign to preach the Gospel in Caesar’s household, the account ends abruptly. This poses a problem for liberals who would late date both the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles to the latter part of the first century or even later. The internal evidence suggests that Acts was written by Luke as a traveling companion of Paul. The abrupt ending implies that Paul was released at this point, which would have been around AD 62.

Prior to the 20th century, New Testament chronologies traditionally put Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome after AD 62. However, there was an archaeological find in 1905 of an inscription that dates Gallio’s proconsulship of Achaia (Acts 18:12). This has had the effect of shifting the traditional dates a couple of years or so earlier. Paul’s trial before Gallio places the first imprisonment under Nero about two years earlier, from around AD 60 to 62 AD. These dates also better fit the events of the Book of Acts, which ends abruptly around that time. Luke does not mention the martyrdom of James, the brother of the Lord and a bishop in the church in Jerusalem, which Josephus places during the Jewish unrest caused by the death of Festus in AD 62. Luke does not mention the fire of Rome in AD 64 or the resulting persecution of Christians under Nero later that year.

Since Acts ends abruptly with the account of Paul’s preaching in Caesar’s household, there is no account of what Paul preached to Nero or the reason why Paul was released. Suetonius, who is otherwise critical of Nero’s despotism, records that in the first part of his reign he often pardoned prisoners and was generally affable toward working class Roman citizens, which certainly describes Paul. AD 62 is also the year that Nero officially wed Poppaea. It is possible that if Poppaea had heard Paul preach, that she would have advocated for him to be released.

Paul presented himself as a rabbi and a Pharisee when the need arose in order to connect with Jews and proselytes familiar with Judaism. To the Gentiles, he presented himself as a Roman citizen and free man. He certainly did so in addressing the pagan Roman procurator Festus and the Herodian rulers, Agrippa and Berenice.

Governor Festus retorted, “You are beside yourself! Much learning is driving you mad!” (Acts 26:24), while King Agrippa countered, “You almost persuade me to become a Christian” (v. 28).

One can imagine Paul giving a similar Gospel presentation of the risen Christ and the hope of the resurrection before Nero, Poppaea and the Roman court, no doubt with a similar reaction. We do not know for certain what Paul preached to Nero, but we can imagine he began his defense as he did before.

My manner of life from my youth, which was spent from the beginning among my own nation at Jerusalem, all the Jews know. They knew me from the first, if they were willing to testify, that according to the strictest sect of our religion I lived a Pharisee (Acts 26:4,5).

Paul might have explained that he was a Roman citizen who had always obeyed the civil magistrate’s law according to the message in Romans 13:1-6. We might even imagine that Paul used his “athlete” analogy to describe the contest of faith.

Do you not know that those who run in a race all run, but one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may obtain it. And everyone who competes for the prize is temperate in all things. Now they do it to obtain a perishable crown, but we for an imperishable crown (1 Corinthians 9:24,25).

Paul most likely would have preached that he was “free” as a Roman citizen and “free” from the curse of the Law as an ambassador of Christ. He probably concluded as he had done before Festus and Agrippa.

“I would to God that not only you, but also all who hear me today, might become both almost and altogether such as I am, except for these chains” (Acts 26:29).

In the final reckoning, Paul committed no crime according to Roman law. It must have seemed odd to Nero to have a “prisoner” so highly esteemed by his own household who appeared in the imperial court not to defend himself, but to defend the Gospel of a messianic sect of Jews.

It may have simply been that Nero the self-described “artist and poet” — champion of the Greek Olympics and patron of the Jewish actor Aliturus — found Paul’s testimony eloquent and entertaining.

Since the Apostle Paul’s imprisonment took place during the years when Poppaea was known for advocating for the Jews on at least two recorded occasions, it is also possible that Nero may have been swayed by Poppaea in this case.

J.B. Lightfoot doubted that Poppaea Sabina would have advocated for Paul, but would have been more inclined to take the side of the synagogue Jews of Rome in favor of punishment. Lightfoot makes the argument that since the Jews of Rome were opposed to Paul, Poppaea would have shared their revulsion to the Gospel.

More plausible is the idea that Poppaea, instigated by the Jews, might have prejudiced the emperor against an offender whom they hated with a bitter hatred. Doubtless she might have done so. But, if she had interfered at all, why should she have been satisfied with delaying his trial or increasing his restraints, when she might have procured his condemnation and death? The hand reeking with the noblest blood of Rome would hardly refuse at her bidding to strike down a poor foreigner, who was almost unknown and would certainly be unavenged. From whatever cause, whether from ignorance or caprice or indifference or disdain, her influence, we may safely conclude, was not exerted to the injury of the Apostle (J.B. Lightfoot, Epistle to the Philippians, “Order of the Epistles of the Captivity”).

On the other hand, the account of Acts records that when Paul preached the Gospel to the synagogue Jews of Rome they were not universally opposed to his message. Acts 28 simply states that “some were persuaded … and some disbelieved.”

Further, Paul was treated well as a Roman citizen who had appealed to Caesar. He lived “in his own rented house and received all who came to him.” The Epistle to the Romans was probably composed from Corinth about a year prior to the time of Paul’s arrest in Jerusalem. Romans 16 shows an intimate familiarity with the Christians who were living in Rome, and as Lightfoot and others have argued, some may have been members of the royal family, slaves and freedmen. If Paul was among Caesar’s household for two whole years, there is a high degree of likelihood that Poppaea knew of him. With her interest in Judaism, how could she not?

Since Poppaea was a “God-fearer,” as Josephus called her, then it is likely she would have been positively affected by Paul’s teaching. God-fearers were of great importance to the growth of the early Church. These were Gentiles who shared religious ideas with Jews to some degree. However, they were not converts to Judaism, but a separate community interested in Jewish religious teaching and practices. Conversion to Judaism would require adherence to all of the Law of Moses, which included numerous prohibitions – such as dietary laws, circumcision, Sabbath observances, participation in the festivals at Jerusalem at least two times a year – which would have been difficult for most people of the Greco-Roman world. Paul’s message of the Gospel of grace was attractive to God-fearers because it did not necessitate an adherence to dietary and ceremonial laws of the Jews in order to be justified before God. So even if Poppaea was not converted to Christ, she may have seen Paul as a wise rabbi who was spreading the Good News throughout the world.

Since there is no description of this meeting in the Book of Acts, it is likely that Luke was not present or he finished his account shortly before Paul was set free.

It is only evident that Paul had a trial in Rome and that he stood before Nero face to face. In 2 Timothy 4:16, he makes mention of his “first answer,” that is, his “first apology” – which was not an apology in the sense of an “excuse” for his conduct – rather the Greek word apologia means a plea or a defense of the faith. This “first answer” may have been his defense in AD 62. However, I think it is more likely that he was referring to another meeting with Nero after his second imprisonment in Rome. We can safely assume that Paul had at least two face to face meetings with Nero.

In any case, the timing of Paul’s release in AD 62 was providential, since about 18 months later the Great Fire of Rome occurred – an event which altered the course of history.

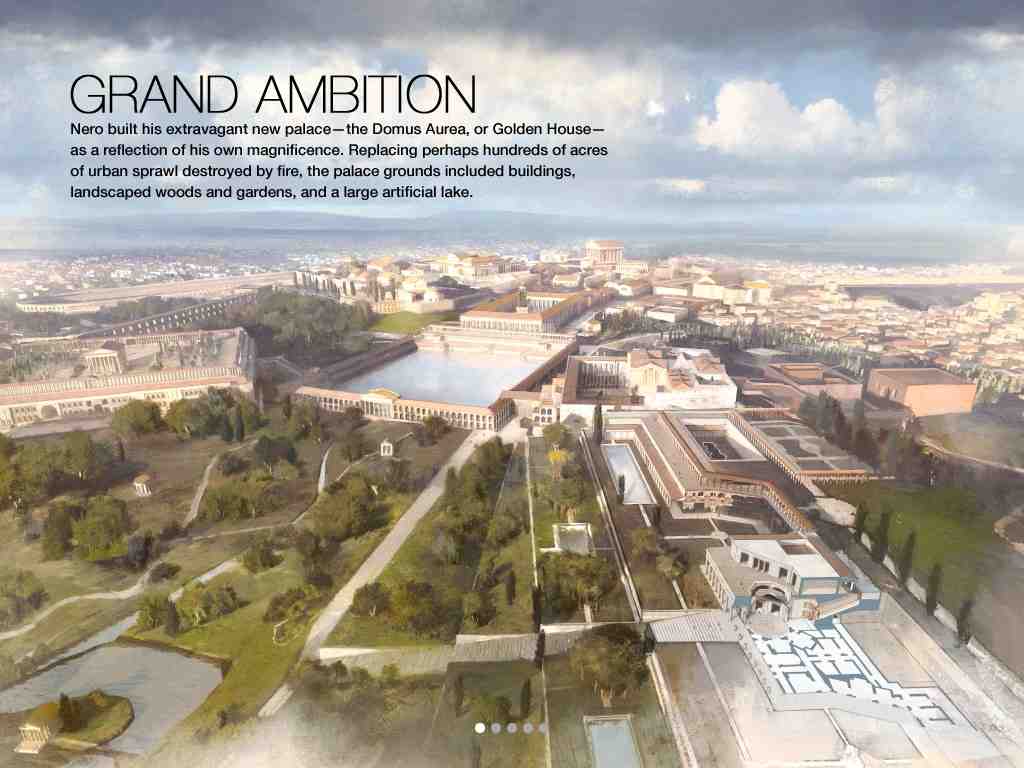

What was Nero’s Golden House?

On July 19th, AD 64, a fire raged throughout the city of Rome for six full days consuming the greater part of the city. The popular image of Nero “fiddling while Rome burned” is probably without basis. When the fire broke out, Nero was at his summer villa on the coast of Italy at Antium about 35 miles from Rome. Nero immediately returned and began relief measures. However, Nero’s popularity had waned by this time and a rumor started that he stood on his rooftop playing his lyre and singing about the destruction of Troy as he watched the city burn.

By the sixth day enormous demolitions had confronted the raging flames with bare ground and open sky, and the fire was finally stamped out.… This new conflagration caused additional ill-feeling because it started on Tigellinus’ estate in the Aemilian district. For people believed that Nero was ambitious to found a new city to be called after himself. Of Rome’s fourteen districts only four remained intact. Three were leveled to the ground. The other seven were reduced to a few scorched and mangled ruins (Tacitus, Annals XV, 40).

Many people by this time saw Nero as a homicidal maniac who had his own mother killed five years earlier. Some believed he had ordered the fire started, especially after he began to use the land cleared by the fire to build his “Golden House,” or Domus Aurea, and the surrounding pleasure gardens in the months following the catastrophe. While the common people were free to enjoy the public gardens at the center of Nero’s Golden House, the extravagance of the palace caused consternation.

The Domus Aurea was designed as a place of entertainment. It was a pleasure palace of 300 rooms without any sleeping quarters, while Nero’s own palace remained on the Quirinal Hill. The Domus Aurea covered parts of the slopes of three of the seven hills of Rome, with a man-made lake at the center, the estimated size of the Domus Aurea was over 300 acres, while others estimate its size to have been under 100 acres. Suetonius describes the complex as a countryside in the city. The outside of the palace was covered in gold leaf and the inside rooms were adorned with marble, precious stones and cut gems, with mosaics and many frescoes by the Roman Empire’s greatest artists. The artwork of the Golden House inspired later Renaissance artists when it was accidently rediscovered in the 15th century under centuries of landfill.

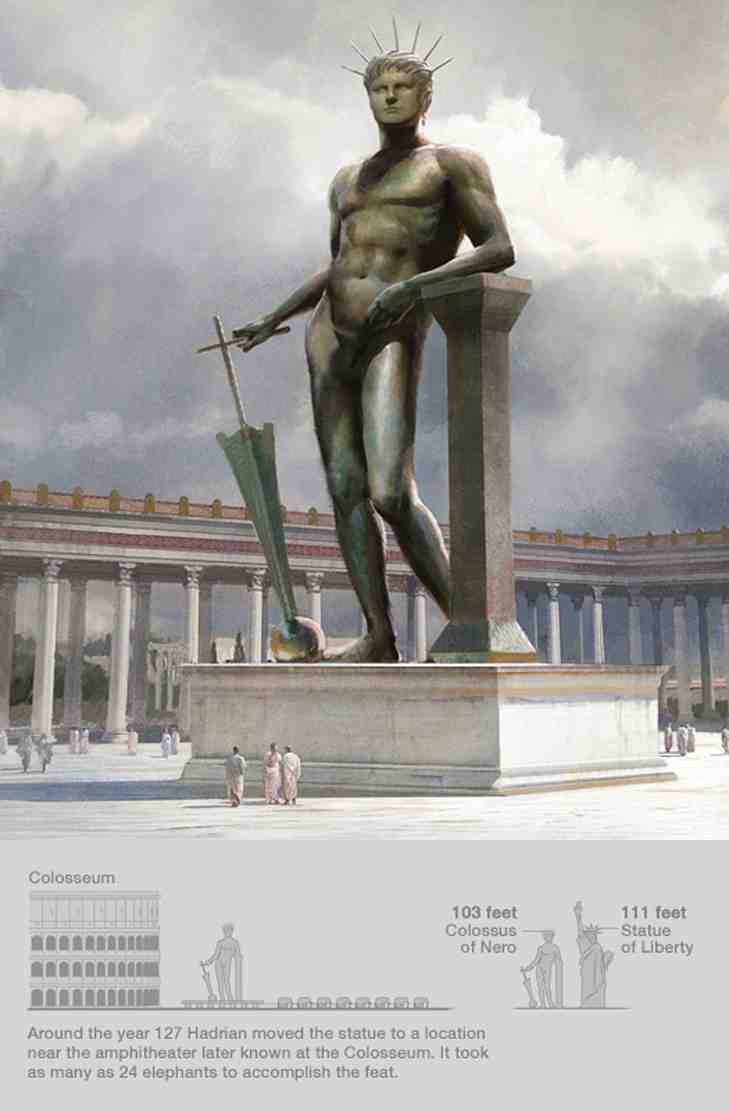

At the center of the public gardens, Nero also commissioned a colossal 95-foot high bronze statue of himself, the Colossus Neronis, almost as high as the Statue of Liberty. This statue represented Nero as the sun god. The face of the statue was modified after Nero’s death during Vespasian’s reign to make it truly a statue of the god Sol. The later Roman Emperor Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheater. This building may have later taken the name Colosseum after the statue of Nero, and not, as some believe, because of the sheer size of the arena. The construction of the Golden House is believed to have taken several years, and parts were still being finished at the time of Nero’s death.

When the edifice was finished in this style and he dedicated it, he deigned to say nothing more in the way of approval than that he was at last beginning to be housed like a human being (Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 31).

When Nero began to build the Golden House, he had additional land cleared by setting smaller fires. This caused many to suspect Nero had wanted the land for himself all along. As the public consternation grew, so did the rumors that Nero started the fire. Nero looked for a scapegoat to deflect his guilt and settled on the Christians. This began the first Roman persecution of the Church that went on for three-and-a-half years. To take John’s “42 months” (Revelation 13:5) exactly literally, we can date the persecution as beginning in December, AD 64 and continuing to Nero’s death on June 9th, 68.

Nero also needed a way to finance his Golden House while simultaneously deflecting the accusations of arson away from himself. Perhaps coinciding with the timing of his plan to frame the Christians as the cause of the fire, Nero began to devalue the silver coins in this year. The Roman “tribunician year” traditionally began on December 10th, which nearly coincided with Nero’s birthday on December 15th. Metallurgists have determined that Nero began to debase the value of silver coins by adding a significant amount of copper beginning in AD 64. The silver taken from these debased coins was used to finance the building of the Golden House.

Suetonius, who was severely critical of Nero, as one given to the most murderous tendencies and all sorts of unnatural lusts, lists the punishment of the Christians among several of Nero’s more admirable accomplishments.

Punishments were also inflicted on the Christians, a sect professing a new and mischievous religious belief (Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 16).

Tacitus shows more sympathy in describing the horrific tortures the Christians suffered and gives details of how the depraved emperor lit his gardens at night with the burning corpses of Christians tarred with pitch.

But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular.

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed (Tacitus Annals XV. 44, bold emphasis mine).

In the summer of AD 65, about a year after the Great Fire, Poppaea was pregnant with what might have become Nero’s only heir. She began to scream at Nero over his spending too much time at the chariot races. Nero kicked her and she began to hemorrhage, or some accounts stated that he repeatedly jumped on her stomach until she was dead. The fact that Poppaea’s body was embalmed and not cremated according to Roman custom is often used as evidence that she had embraced Judaism or some foreign religion. Shortly afterward, Nero had her son by her former husband Rufrius put to death. After Poppaea’s death, Nero descended into complete madness. He engaged in every type of sexual perversion imaginable including having a young male freedman castrated, dressing him as Poppaea and pretending that she remained alive.

Either it was during the time when the Gospel was being preached in Caesar’s household, or a few years after, that Nero became convinced of a prophecy about a king who would rule the whole world from the east – some said from the city of Jerusalem. It is unclear where he first heard this prophecy. It may have come from his own soothsayers and astrologers, Poppaea’s knowledge of Judaism, one of Paul’s converts in Nero’s household, or the preaching of the Apostle Paul himself.

Some preterist writers mention that Nero killed his pregnant wife Poppaea and make note that Nero was the Roman emperor during Paul’s stay in Rome from AD 60 to 62. However, no one has advanced the thesis that Nero may have become knowledgeable of the Hebrew Scriptures through either Poppaea or Paul. Evidently, Nero twisted the prophecies of Scripture and deceived himself into thinking that he was the promised Messiah prophesied by Daniel, the king of the world who would rule from Jerusalem.

According to Josephus, as soon as Nero took the throne in AD 54, many false Messiahs entered Jerusalem. Great natural disasters began to take place, famines, pestilence and earthquakes. This set the stage, according to Matthew 24, for a rebellion against Roman rule and the invasion of Judea by Roman forces in AD 66.

According to Suetonius, Nero believed that a prophecy from the East foretold of his coming as a world ruler. This was confirmed by his astrologers, but it is uncertain what is being referred to. Suetonius gives the following information saying that the Jerusalem prophecy came from “astrologers.” However, we know that the Romans were aware of the messianic prophecies of the Bible.

Nero’s astrologers had told him that he would one day be removed from public office, and were given the famous reply:

“A simple craft will keep a man from want.”

This referred doubtless to his lyre-playing which, although it might be only a pastime for an emperor, would have to support him if he were reduced to earning a livelihood. Some astrologers forecast that, if forced to leave Rome, he would find another throne in the East; one or two even particularized that of Jerusalem (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 40).

In recording that Nero had thoughts to move his throne from Rome to Jerusalem, Suetonius reveals that this was a motivation for Nero’s war on Judea.

An ancient superstition was current in the East, that out of Judea would come the rulers of the world. This prediction, as it later proved, referred to two Roman Emperors, Vespasian and his son Titus; but the rebellious Jews, who read it as referring to themselves, murdered their Procurator, routed the Governor-general of Syria when he came down to restore order, and captured an Eagle. To crush this uprising, the Romans needed a strong army under an energetic commander, who could be trusted not to his plenary powers. The choice fell on Vespasian. He had given signal proof of energy and nothing, it seemed, need be feared from a man of such modest antecedents. Two legions, with eight cavalry divisions and ten supernumerary battalions, were therefore dispatched to join the forces already in Judea; and Vespasian took his elder son, Titus, to serve on his staff (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Vespasian” 4).

Tacitus also relates the prophecy of messianic expectation. It is likely that Tacitus learned this from conferring with Josephus. Both were in Rome at the time they wrote their histories.

The majority [of the Jews] firmly believed that their ancient priestly writings contained the prophecy that this was the very time when the East should grow strong and that men starting from Judea should possess the world. This mysterious prophecy had in reality pointed to Vespasian and Titus, but the common people, as is the way of human ambition, interpreted these great destinies in their own favour, and could not be turned to the truth even by adversity (Tacitus, Histories, V.13).

This begs the question, which “ancient priestly writings” were Suetonius and Tacitus referring to? In all likelihood, it was the prophecy of Daniel 2:44.

And in the days of these kings the God of heaven will set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed; and the kingdom shall not be left to other people; it shall break in pieces and consume all these kingdoms, and it shall stand forever.

It is possible that Nero knew the Daniel prophecy from his wife, Poppaea, or had even heard of the Mount Olivet Discourse through the Apostle Paul’s teaching. Nero had already declared himself to be a god. Now he wanted to move the seat of the capital from Rome to Jerusalem. But after the events that took place from AD 64 to 66, Nero became an enemy of both Christians and Jews.

Nero’s reign occurred during a time frame when messianic fervor was at a fever pitch among the Jews. Like most Romans, Nero was probably unable to discern one messianic Jewish sect from another. The blame for the Great Fire of Rome was laid at the feet of Christians, but even Tacitus writing a generation later notes that Christianity was a “superstition” that originated in Judea. Nero likely saw the rebellion of messianic Jews at Jerusalem as part of the same superstition. After Nero killed Poppaea in AD 65, combined with his resulting denial and bitterness over the mishap, the rebellion in Judea in AD 66 must have led him to think that the prophecies of an “eastern king” were a threat to his sovereignty – although he hoped that this applied to himself.

Gessius Florus was the Roman procurator of Judea from 64 until 66. Ironically, he was appointed by the Emperor Nero due to Poppaea’s friendship with his wife. He was noted for his public greed and injustice to the Jews, and is blamed by Josephus as being the primary cause of the Great Jewish Revolt of AD 66. Gessius Florus and the Roman general Cestius Gallus failed to put down an uprising that started as a tax revolt. In a short time, this turned into a major war. Nero then sent one of the greatest generals in the Roman Empire, Vespasian, to attack Judea in AD 67.

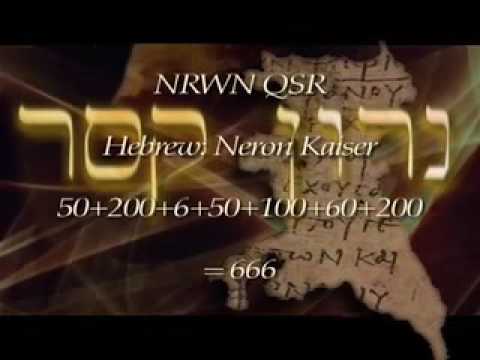

What is the evidence that 666 equals the number of Nero?

Much has been written by preterists that “Neron Caesar” (Nron Qsr, נרון קסר) adds up to 666 when spelled in Hebrew letters. In ancient cultures, numerals were expressed by certain letters of the alphabet. In fact, our modern numerals are derived from Arabic letters. Since each letter in an ancient language had a numerical value, a person’s name could be added up to equal a certain number. Apparently, counting the number of the “Beast” Nero was a popular past-time even among pagans. Suetonius wrote that a piece of graffiti often scrawled on the walls of the empire had the following saying.

Count the numerical values,

Of the letters in Nero’s name,

And in “murdered his own mother”:

You will find their sum is the same.

The letters of Nero’s name in Greek when converted into numerals, had the sum value of 1005; and so had the letters of “murdered his own mother.” This shows that it was a well-known practice to use numerical “code” to speak of this dictator.

That Nero was nicknamed the “Beast ” is attested to in several ancient sources. There are other instances of cryptograms that were used to refer to the insane emperor, who had killed his mother. The Sibylline Oracles had done this as well calling Nero a “terrible snake” and citing that Nero’s name had “fifty as an initial.”

One who has fifty as an initial will be commander, a terrible snake, breathing out grievous war, who one day will lay hands on his own family and slay them, and throw every-thing into confusion, athlete, charioteer, murderer, one who dares ten thousand things. He will also cut the mountain between two seas and defile it with gore. But even when he disappears he will be destructive. Then he will return declaring himself equal to God. But he will prove that he is not. Three princes after him will perish at each others’ hands.

The Sibylline Oracles, which are Greek language pseudo-prophecies written after the fact, may have drawn on the idea that the name of Nero equaled the number of the Beast. In any case, the Apostle John was not the only writer to use cryptogram as the name of Nero. Criticizing a mad emperor in writing was a dangerous business. So cryptic references were necessary, although some were more obvious than others.

In support of this hypothesis, there is also a textual variant in some early copies of Revelation that has the reader count the number of the Beast as “616” – “Caesar Nero” – and not the Aramaic “666” – “Caesar Neron.” The difference is in the Latin versus the Aramaic spelling of Nero’s name. Dropping the last “N” subtracted the number 50 from the total. This variant has been known from the mid-second century and was mentioned by the Church Father Irenaeus in his writings.

Another attempt to make Nero’s name equal the variant “616” is the Liber genealogus, a chronology written in Latin by an unknown North African Donatist Christian in the fifth century. It uses the Latin spelling, not the Hebrew. It also advocates a Nero Redivivus futurist theory, not a preterist interpretation. Literally, “Nero Revived,” this was a popular fable among Jews and Christians that Nero would rise from the dead and appear once again as an Antichrist world ruler who would touch off events that would lead to a messianic kingdom.

Citing a portion of Revelation 13:18, paragraphs 614-620 of the version that was written in AD 438 states that the letters of Nero’s name are to be used in calculating the number of the Beast (Francis X. Gumerlock, Westminster Seminary Journal 68 (2006):347-360, “Nero Antichrist: Patristic Evidence of the Use of Nero’s Name in Calculating the Number of the Beast”).

When was Paul’s second imprisonment under Nero?

Church tradition has Paul coming a second time to Rome along with Peter at some point after AD 64. Either they were arrested during Nero’s persecution from AD 64 to 68 or they had already been in Rome preaching when the persecution of Christians broke out after the Great Fire in AD 64. Since the Book of Acts ends abruptly a few years before the events of AD 64, we have to use the later Epistles of Paul and the writings of the Church Fathers to piece together a chronology of what may have happened in the five years between AD 62 and 67. The following synopsis by William Killen presents the traditional view of the Church Fathers on Paul’s activities after his first imprisonment in Rome.

It is probable that Paul, after his release, accomplished his intention of visiting the Spanish Peninsula…. In all likelihood, he now once more visited Jerusalem, travelling by Corinth, Philippi, and Troas, where he left for the use of Carpus the case with the books and parchments which he mentions in his Second Epistle to Timothy (4:13). Passing on then to Colossae, he may have visited Antioch in Pisidia and other cities of Asia Minor, the scenes of his early ministrations; and reached Jerusalem by way of Antioch in Syria. He perhaps returned from Palestine to Rome by sea, leaving Trophimus sick at Miletum in Crete (2 Timothy 4:20). The journey did not probably occupy much time; and, on his return to Italy, he seems to have been immediately incarcerated. His condition was now very different from what it had been during his former confinement; for he was deserted by his friends, and treated as a malefactor.

When he wrote to Timothy he had already been brought before the judgment-seat, and had narrowly escaped martyrdom. “At my first answer,” says he, “no man stood with me, but all men forsook me. I pray God that it may not be laid to their charge. Notwithstanding the Lord stood with me and strengthened me, that by me the preaching might be fully known, and that all the Gentiles might hear; and I was delivered out of the mouth of the lion” (2 Timothy 4:16,17). The prospect, however, still continued gloomy; and he had no hope of ultimate escape. In the anticipation of his condemnation, he wrote those words so full of Christian faith and heroism, “I am now ready to be offered, and the time of my departure is at hand. I have fought a good fight – I have finished my course – I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, shall give me in that day, and not to me only, but unto all them also that love his appearing” (2 Timothy 4:6-8) (William Dool Killen, The Ancient Church, “Paul’s Second Imprisonment, and Martyrdom; Peter, his Epistles, his Martyrdom, and the Roman Church”).

Traditionally, June 29th, AD 67 is the date of the martyrdom of Peter and Paul at Rome. The account of the deaths of the Apostles at Rome is early and well-attested. Clement of Rome, who wrote his Epistle to the Corinthians, probably written around AD 96, gave the earliest witness – possibly an eyewitness account since Clement was an early bishop in the church at Rome.

But not to dwell upon ancient examples, let us come to the most recent spiritual heroes. Let us take the noble examples furnished in our own generation. Through envy and jealousy, the greatest and most righteous pillars [of the Church] have been persecuted and put to death. Let us set before our eyes the illustrious apostles. Peter, through unrighteous envy, endured not one or two, but numerous labours, and when he had finally suffered martyrdom, departed to the place of glory due to him. Owing to envy, Paul also obtained the reward of patient endurance, after being seven times thrown into captivity, compelled to flee, and stoned. After preaching both in the east and west, he gained the illustrious reputation due to his faith, having taught righteousness to the whole world, and come to the extreme limit of the west, and suffered martyrdom under the prefects. Thus was he removed from the world, and went into the holy place, having proved himself a striking example of patience. To these men who spent their lives in the practice of holiness, there is to be added a great multitude of the elect, who, having through envy endured many indignities and tortures, furnished us with a most excellent example (1 Clement 5,6, bold emphasis mine).

A short apologetic treatise by the Church Father Lactantius, “Of the Manner in Which the Persecutors Died,” was written shortly before the Council of Nicea in the early fourth century. It mentions that Nero was in fact called a “beast” and attempts to refute the then popular “Nero Redivivus” theory.

His apostles were at that time eleven in number, to whom were added Matthias, in the room of the traitor Judas, and afterwards Paul. Then were they dispersed throughout all the earth to preach the Gospel, as the Lord their Master had commanded them; and during twenty-five years, and until the beginning of the reign of the Emperor Nero, they occupied themselves in laying the foundations of the Church in every province and city.

Since Nero came to power on October 13, AD 54, “twenty-five years” is exactly right if we assume that Jesus’ ascension was in AD 30 and the New Year was counted in the fall in most Roman provinces, usually in September. October AD 54 would have been the beginning of the 25th year since Christ’s ascension.

And while Nero reigned, the Apostle Peter came to Rome, and, through the power of God committed unto him, wrought certain miracles, and, by turning many to the true religion, built up a faithful and steadfast temple unto the Lord. When Nero heard of those things, and observed that not only in Rome, but in every other place, a great multitude revolted daily from the worship of idols, and, condemning their old ways, went over to the new religion, he, an execrable and pernicious tyrant, sprung forward to raze the heavenly temple and destroy the true faith. He it was who first persecuted the servants of God; he crucified Peter, and slew Paul: nor did he escape with impunity; for God looked on the affliction of His people; and therefore the tyrant, bereaved of authority, and precipitated from the height of empire, suddenly disappeared, and even the burial-place of that noxious wild beast was nowhere to be seen. This has led some persons of extravagant imagination to suppose that, having been conveyed to a distant region, he is still reserved alive; and to him they apply the Sibylline verses concerning

“The fugitive, who slew his own mother, being to come from the uttermost boundaries of the earth;”

as if he who was the first should also be the last persecutor, and thus prove the forerunner of Antichrist! But we ought not to believe those who, affirming that the two prophets Enoch and Elias have been translated into some remote place that they might attend our Lord when He shall come to judgment, also fancy that Nero is to appear hereafter as the forerunner of the devil, when he shall come to lay waste the earth and overthrow mankind (Lactantius, Divine Institutes, Book IV, bold emphasis mine).

Was the persecution of Christians under Nero localized or empire-wide?

While there is little to go on, many modern Church historians assume that the Neronian persecution was localized to Rome. Therefore, preterists have to make the case to explain why John could have been arrested in Ephesus and exiled to Patmos. However, there is more ancient contemporary testimony for the Neronian persecution than for the persecution under Domitian. Tacitus, Clement of Rome and Lactantius use the words “an immense multitude” and “multitudes” in describing the Christians who were put to death by Nero’s persecution.

The oldest testimonies closest to the source record a great number of Christians being martyred. Coupled with the fact that the Apostolic Church was already suffering ongoing persecutions from the Jews, it is not a stretch to imagine the iron claws of Rome stretching into Ephesus to arrest the Apostle John.

Lactantius’ purpose in writing on the sixth Roman Caesar was to refute the Nero Redivivus theory. Lactantius was a futurist, but saw the idea that Nero would rise from the dead to be revealed as the future Antichrist as a misguided superstition. Yet he recognized that Nero fit the description of the Beast of Revelation. Nero was the Roman emperor who sent Vespasian to conquer the city of Jerusalem that resulted in the Temple being destroyed. “Not one stone here shall be left upon another, which will not be torn down” (Matthew 24:2). What is interesting about Lactantius’ account is that he connects the razing of the Temple with the fact that Nero had also “sprung forward to raze the heavenly temple and destroy the true faith” – meaning he persecuted the Church founded by Christ and killed many Christians including the Apostles Peter and Paul.

Lactantius also has Peter and Paul preaching at Rome reiterating the words of the Daniel and Jesus that the time was at hand for foretold “abomination that causes desolation” to come to pass (Daniel 12:11; Matthew 24:15; Luke 21:20).

But He also opened to them all things which were about to happen, which Peter and Paul preached at Rome; and also said that it was about to come to pass, that after a short time God would send against them a king who would subdue the Jews, and level their cities to the ground, and besiege the people themselves, worn out with hunger and thirst. Then it should come to pass that they should feed on the bodies of their own children, and consume one another. Lastly, that they should be taken captive, and come into the hands of their enemies, and should see their wives most cruelly harassed before their eyes, their virgins ravished and polluted, their sons torn in pieces, their little ones dashed to the ground; and lastly, everything laid waste with fire and sword, the captives banished forever from their own lands, because they had exulted over the well-beloved and most approved Son of God. And so, after their decease, when Nero had put them to death, Vespasian destroyed the name and nation of the Jews, and did all things which they had foretold as about to come to pass (Lactantius, Divine Institutes, Book IV).

Lactantius assumes that in preaching the Gospel, Peter and Paul would have included the Mount Olivet Discourse. There is obviously some embellishment here in an account written a few centuries after the event. However, Lactantius knew that Peter and Paul preached in Rome and were martyred by Nero. He supposed that they had preached the full contents of the Gospel. The prophecy that Rome would send legions to Judea and “level their cities” follows the Mount Olivet Discourse together with other details found in Josephus’ History of the Wars of the Jews.

Paul’s arrest was probably prior to Nero’s departure for Greece in the fall of AD 67, as he called for Timothy and Mark to come to Rome “before winter” in his Second Epistle to Timothy.

Only Luke is with me. Get Mark and bring him with you, for he is useful to me for ministry. And Tychicus I have sent to Ephesus. Bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas when you come – and the books, especially the parchments … Do your utmost to come before winter (2 Timothy 4:11-13,21).

The authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews is a matter of controversy. I am of the opinion that it was composed by Paul and Luke during the second imprisonment at Rome and polished by Timothy or another scribe, such as Clement of Rome. The purpose of Hebrews is to explain the covenantal shift that had occurred at the coming of Christ and to ready the Hebrew Christians for the soon coming destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem. Since most Christians at this point were ethnic Jews, they were not to put their hopes in the types and shadows represented in Temple worship, but in Christ alone.

Paul does not mention Peter in 2 Timothy, so if the Peter came to Rome, it was after Paul, perhaps to meet up with his disciple Mark, whom he mentions as being with him in 1 Peter 5:13. At Rome, Peter probably wrote his Second Epistle explaining that he was approaching his death and warning about the wrath of God’s coming judgment.

But the day of the Lord will come as a thief in the night, in which the heavens will pass away with a great noise, and the elements will melt with fervent heat; both the earth and the works that are in it will be burned up (2 Peter 3:10).

The key to understanding much of the apocalyptic language 2 Peter 3 is to know that the sense of impending judgment is related to the coming destruction of Jerusalem. In fact, the phrase, “the elements will melt with fervent heat,” most likely refers to the Temple at Jerusalem and the sacrificial system. Each time the word stoicheion is used in the Pauline epistles, it refers to “elementary principles” related to doctrines or modes of worship that were passing away with the coming of the New Covenant (cf. Galatians 4:3,9; Colossians 2:8,20; Hebrews 5:12). As in his sermon in Acts 2, Peter is characteristically speaking with a sense of urgency for his immediate audience, while also keeping in view “day of the Lord” that will be yet to come – or the Final Judgment.

After Mark came to Rome at the behest of Paul, he probably wrote the Gospel According to Mark. The tradition of the Church Fathers, beginning with Papias of Hierapolis, testifies that Mark wrote down the Gospel preached by the Apostle Peter from memory.

Mark having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately whatsoever he remembered. It was not, however, in exact order that he related the sayings or deeds of Christ. For he neither heard the Lord nor accompanied Him. But afterwards, as I said, he accompanied Peter, who accommodated his instructions to the necessities [of his hearers], but with no intention of giving a regular narrative of the Lord’s sayings. Wherefore Mark made no mistake in thus writing some things as he remembered them. For of one thing he took special care, not to omit anything he had heard, and not to put anything fictitious into the statements (Papias, Fragments).

Most modern scholars concur that Mark probably wrote from Rome and was addressing a Greco-Roman audience. Mark explains Aramaic phrases and customs and uses a number of Latin terms. Although many modern theologians hold to a “Marcan Priority Hypothesis,” with Matthew and Luke drawing on materials from Mark, the view for most of Church history was that the four Gospel accounts were written independently. Clement of Alexandria taught that Mark was a later conflation of Matthew and Luke. The internal evidence from the New Testament and testimony from the Church Fathers indicates that this may be true.

Was the Book of Revelation written while Nero was the Emperor?

Another controversy that rages about the issue of preterism is the date when John’s Book of Revelation was written. Many suppose it was written late, when John would have been an extremely old man, during the second persecution of the Christians under Domitian that ended in AD 96. Yet John actually gives two strong internal indicators that tell us when he is writing.

First, he never once mentions that the Temple at Jerusalem has been destroyed in the past tense. Every time he mentions the Temple, it is still standing (cf. Revelation 11). Since the Temple was destroyed in 70 AD, he would have had to be writing before then.

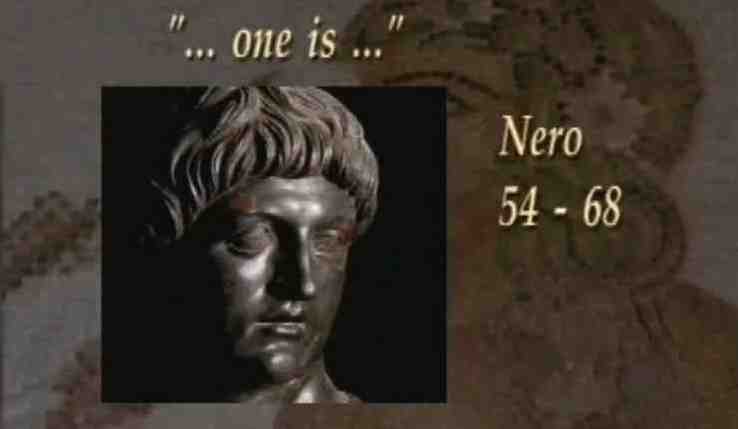

Second, the most direct indication of when the Book of Revelation was written, points to a king who “is.”

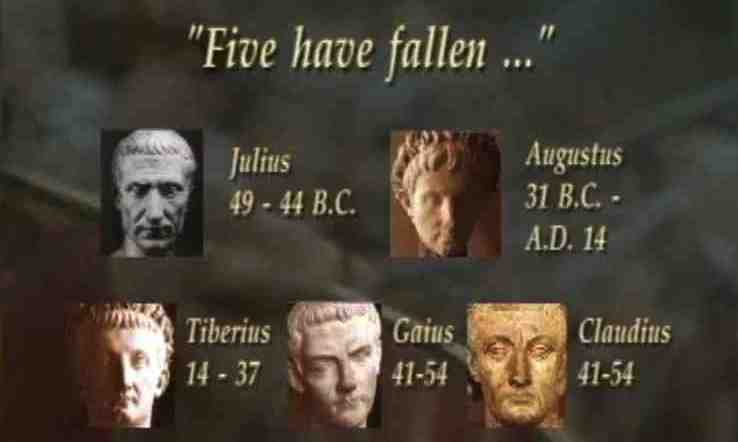

There are also seven kings. Five have fallen, one is, and the other has not yet come. And when he comes, he must continue a short time (Revelation 17:10, bold emphasis mine).

If we use the line of Roman kings given by Suetonius and Josephus, these are:

1. Julius

2. Augustus

3. Tiberius

4. Caligula

5. Claudius

6. Nero

The sixth king who “is” at the time of John’s writing was Nero.

There are several traditions that hold to an early date of the writing of Revelation, prior to the death of Nero.

1. The fourth century Church Father, Epiphanius of Salamis, wrote that Revelation was written during the time of “Claudius Caesar.” He could have been referring to either Claudius or Nero since Nero’s full name upon his adoption was “Nero Claudius Caesar Drussus Germanicus.” His throne name was “Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus.” In either case, this supports an early date for the writing of Revelation.

2. The Muratorian canon, a list of New Testament books compiled in about AD 170, states that the letters of Paul were seven in number and followed John’s example of the letters to the seven churches of Asia Minor in Revelation 1-3. This would have put the writing of Revelation prior to the death of Paul, which took place in the reign of Nero.

3. Tertullian of Carthage places John’s banishment to Patmos in the immediate context of Nero’s persecution.

4. Clement of Alexandria writes that the ministries of Jesus’ Apostles “end with Nero.”

5. Several early Syriac translations of the Bible all contain a “superscript” or introduction, “The Revelation, which was made by God to John the Evangelist, in the island of Patmos, to which he was banished by Nero the Emperor.”

John was probably writing in late AD 64 or 65. Nero’s persecution of the Church may have lasted a full 42 months, or the 42 months could be the counted from the time John began to write Revelation, from the end of the year 64 to Nero’s death in June 68.

And he was given a mouth speaking great things and blasphemies, and he was given authority to continue for forty-two months. Then he opened his mouth in blasphemy against God, to blaspheme His name, His tabernacle, and those who dwell in heaven. It was granted to him to make war with the saints and to overcome them. And authority was given him over every tribe, tongue, and nation (Revelation 13:5-7, bold emphasis mine).

The Book of Acts, Romans 16, Philippians 4 and several early Church traditions indicate that Nero heard the Gospel preached by the Apostle Paul – or at least knew of a prophecy that the king of the world would come from Jerusalem – prior to the Great Fire of Rome. The Gospel According to Luke, which was thought by the Church Fathers to be Paul’s Gospel, contained the Mount Olivet Discourse as did the Gospel According to Mark, which was thought to be Peter’s Gospel. Lactantius and others inferred that this drew Nero’s ire.

However, the Gospel According to John does not contain the Mount Olivet Discourse passage. It could be inferred that John was merely banished by the Roman authorities and not executed because he did not preach openly about the coming tribulation except in veiled terms. In the Gospel According to John, which may have been written after the deaths of Peter and Paul in AD 67, but prior to the destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem in AD 70, it is inferred that Peter has already died, while John would “remain till I come.”

Jesus said to him, “Feed My sheep. Most assuredly, I say to you, when you were younger, you girded yourself and walked where you wished; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish.” This He spoke, signifying by what death he would glorify God. And when He had spoken this, He said to him, “Follow Me.”

Then Peter, turning around, saw the disciple whom Jesus loved following, who also had leaned on His breast at the supper, and said, “Lord, who is the one who betrays You?” Peter, seeing him, said to Jesus, “But Lord, what about this man?”

Jesus said to him, “If I will that he remain till I come, what is that to you? You follow Me.”

Then this saying went out among the brethren that this disciple would not die. Yet Jesus did not say to him that he would not die, but, “If I will that he remain till I come, what is that to you?”

This is the disciple who testifies of these things, and wrote these things; and we know that his testimony is true (John 21:17-24).

This has been interpreted in various ways. According to early Church tradition, Paul was beheaded, which was the mode of execution for a Roman citizen. Peter’s mode of execution was to be crucified. Crucifixion was a common form of punishment for slaves and non-Roman citizens, so the crucifixion of Peter is historically likely. The reference that Peter would be crucified in found in Jesus admonition, “you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish.” The tradition that Peter was crucified upside down because he was too ashamed to have the same manner of death as the Lord is also entirely possible although it could be a later embellishment.

The question, “If I will that he remain till I come, what is that to you?” refers to John. This is confusing as it seems to indicate that John would remain until the Second Coming of the Lord. But this cannot be the case since John indicates that “Jesus did not say to him that he would not die.” The preterist view has offered the only solution to this cryptic saying that makes any sense. This is most likely John’s reference to the Lord’s “coming in judgment on the city of Jerusalem,” but not the “Second Coming of Jesus.” John may have been the only one of the Twelve Apostles who survived Nero’s persecution, the destruction of the Temple in AD 70, and then a second persecution under the Emperor Domitian who was himself assassinated in AD 96.

What happened to end the persecution of the Church?

Although Nero still remained popular among some of the lower classes, he had become a polarizing figure. The aristocrats and the senators began to conspire against him. This only added to Nero’s paranoia. In his last years, he began to put to death anyone who aroused his suspicion, including his teacher from childhood, Seneca.

There was no family relationship which Nero did not criminally abuse. When Claudius’s daughter Antonia refused to take Poppaea’s place, he had her executed on a charge of attempted rebellion; and destroyed every other member of his family, including relatives by marriage, in the same way (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 36,37).

Tacitus and Suetonius record a comet that was observed after the time of the Great Fire. We know from ancient astronomy that comets appeared in AD 64, 65 and 66, the latter being Halley’s Comet. Tacitus also states that Nero consulted an astrologer and was advised to kill members of the aristocracy to atone for the comet.

Nero was no less cruel to strangers than to members of his family. A comet, popularly supposed to herald the death of some person of outstanding importance, appeared several nights running and greatly disturbed him. His astrologer Balbillus observed that monarchs usually avoided portents of this kind by executing their most prominent subjects and thus directing the wrath of heaven elsewhere; so Nero resolved on a wholesale massacre of the nobility. What fortified him in this decision, and seemed to justify it, was that he had discovered two plots against his life. The earlier and more important one of the two was Piso’s conspiracy in Rome; the other, detected at Beneventum, had been headed by Vinicius. When brought up for trial the conspirators were loaded with three sets of chains. Some, while admitting their guilt, claimed that by destroying a man so thoroughly steeped in evil as Nero, they would have been doing him the greatest possible service. All children of the condemned men were banished from Rome, and then starved to death or poisoned.

After this, nothing could restrain Nero from murdering anyone he pleased, on whatever pretext (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 36,37)

This description indicates that it was likely one of the latter two comets since Suetonius recorded this after the death of Poppaea. At the time of his death, Nero had planned to make over the entire city of Rome renaming it Neropolis.

At last, after nearly fourteen years of Nero’s misrule, the earth rid herself of him. The first move was made by the Gauls under Julius Vindex, their pro-Praetor (Seutonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 40).

Nero began behaving more and more irrationally and some of the Praetorian Guard decided he had to be assassinated. While fleeing a military coup, Nero committed suicide on June 9 AD 68 by stabbing himself with a sword. Rather than be killed by the coup, he killed himself.

He who kills with the sword must be killed with the sword (Revelation 13:10).

Among his last words were, Qualis artifex pereo. This is translated as, “What an artist perishes!” or “So great an artist – dead!”

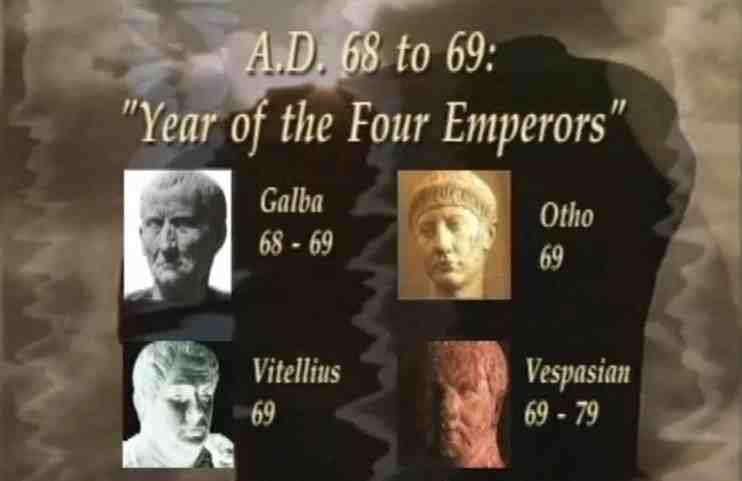

Then came a civil war and the next four emperors, all within the space of one year.

7. Galba

8. Otho

9. Vitellius

10. Vespasian

Seven heads. Ten Horns. The Roman world thought the empire was dead with no one in line from the Julio-Claudian line to take sole rulership of Rome. A civil war ensued and the empire was thrown into chaos for a time.

Was Nero really that bad?

In a word, yes. Josephus and Tacitus wrote that the accounts of Nero’s depravity by other historians were exaggerated, but they agreed that he was a tyrant. Even the poet Lucanus, who wrote of the peace and prosperity under Nero in contrast to previous war and strife, was later involved in a conspiracy to overthrow Nero and was executed. Seneca, Nero’s teacher from the time he was a boy, wrote only positive things about Nero. However, Seneca too was caught up in a plot to assassinate Nero. Although it is questionable whether Seneca was guilty, Nero ordered him to commit suicide – the Roman method of “honor killing.”

Despite the murderous reign of Nero, the devotion to the emperor cult remained strong among a minority, especially in the East. Some persisted in the belief that Nero was not dead and at least three imposters claiming to be Nero appeared. Even twenty years later, a Nero imposter in the eastern province of Parthia gained a following and was extradited to Rome to be executed. This gave rise to the “Nero Redivivus” myth among many Christians and Jews – the belief that Nero would rise from the dead with his deadly head wound healed to rule the world once more as the Antichrist.

Nero died at the age of thirty-two, on the anniversary of Octavia’s murder. In the widespread general rejoicing, citizens ran through the streets wearing caps of liberty, as though they were freed slaves. But a few faithful friends used to lay spring and summer flowers on his grave for some years, and had statues made of him, wearing his fringed gown, which they put up on the Rostra; they even continued to circulate his edicts, pretending he was still alive and would soon return to confound his enemies. What is more, King Vologaesus of Parthia, on sending ambassadors to ratify his alliance with Rome, particularly requested the Senate to honour Nero’s memory. In fact, twenty years later, when I was a young man, a mysterious individual came forward claiming to be Nero; and so magical was the sound of his name in the Parthians’ ears that they supported him to the best of their ability, and were most reluctant to concede Roman demands for his extradition (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, “Nero” 57).

The Babylonian Talmud, written in the second century AD, contains an apocryphal story that has Nero coming to Jerusalem after he fled from Rome.

When Nero arrived in Palestine, he shot arrows in the direction of the four principal points of the compass; but all of them flew toward Jerusalem. A boy whom he asked to recite his Biblical lesson (a usual form of oracle) quoted Ezekiel 25:14, “And I shall take my revenge on Edom through My people Israel; and they shall do unto Edom according to My anger and My wrath,” on hearing which Nero said: “God wishes to wipe His hands [lay the blame] on me” (i.e., “wishes to make me His tool and then to punish me”). He fled and became a convert to Judaism; and from him Rabbi Meïr was descended. This Talmudical story seems to be an echo of the legend that Nero was still alive and would return to reign. Indeed, some pretenders availed themselves of this legend and claimed to be Nero. Oracles prophesying Nero’s return from beyond the Euphrates were current among the Jews; and an apocryphal book of the second century, Ascension of Isaiah, declares that in the last days “Belial shall appear in the form of a man, of the king of unrighteousness, of the matricide.” In Christian legends, Nero was personified as Antichrist (Gotthard Deutsch, S. Mannheimer, “Nero,” JewishEncyclopedia.com).

Even though the majority of sources paint Nero as an insane despot, still there were those who had a favorable view of him. Dio Chrysostom (c. AD 40–120), the Greek philosopher and historian, wrote that the Roman people longed for Nero once he was gone and embraced imposters whenever they appeared.

Indeed the truth about this has not come out even yet; for so far as the rest of his subjects were concerned, there was nothing to prevent his continuing to be Emperor for all time, seeing that even now everybody wishes he were still alive. And the great majority do believe that he still is, although in a certain sense he has died not once but often along with those who had been firmly convinced that he was still alive (Dio Chrysostom, Discourse XXI, On Beauty).

In the wake of Nero’s suicide, it appeared to many that the Roman Empire could not survive after years of misrule and a resulting bitter civil war. Yet in little over a year, the Empire came back with a vengeance under the military strong man, Vespasian. Seemingly, the Great Beast was brought back from the dead.

Nero was the sixth head of the Beast. He was the king referred to as the “little horn” in Daniel 7 and the “sixth” king who “is” at the time John wrote Revelation 13 and 17.

2 Comments

Thanks your you work. This is great information.

Your research and study are very useful. I use this material (along with “In the Days of These Kings”) to support the Preterist view when discussing “End Times” with friends and family. St. Paul’s admonition to “study to show yourself approved” certainly applies to understanding Scripture along with its historical context.