Can the Gospels be authenticated?

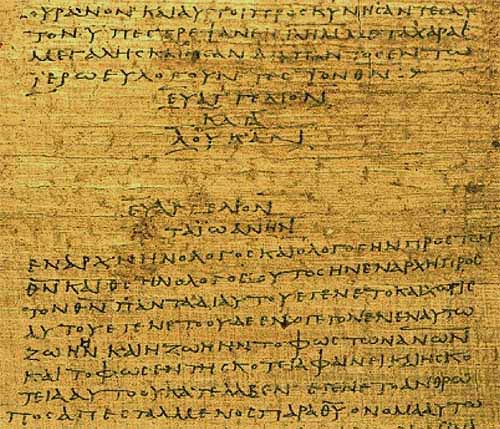

One of the almost universally held notions of liberal theology is that the Gospels are anonymous writings and the names of the authors were not attached to the original manuscripts. Although we do not have the original manuscripts, this is stated as a certain fact. However, the earliest codices are not anonymous. Here is an image of P75, a papyrus codex that was copied at the end of the second century from an earlier copy.

This is the earliest example that we have of a manuscript in which one Gospel ends and another begins. Even if you can’t read Greek, it is clear that the title and author of the two books appear here near the top of the page – the Greek words say: “Gospel according to Luke” and “Gospel according to John.”

So why do the liberals claim the original autographs were anonymous? There are two reasons for this. The first is scientific skepticism. In any hard science, a theory is not proven unless data exists that can confirm a hypothesis. Scientific skepticism doesn’t accept something as fact unless it can be proven. Textual criticism, although not a hard science, uses the same methods. The skeptics will assume the latest date possible until an earlier date can be established. They will assume anonymity or pseudonymity until authorship can be proven. They do not, however, try to prove their position.

When the liberal critics say books are anonymous or too late to be the authentic works of the named authors, they don’t have proof of this. They just don’t accept the evidence to the contrary as compelling. The problem is that others frequently cite this skepticism as fact, when no textual critic is really ever certain of his dating. They simply assume the latest possible dates based on the evidence. However, there are a surprising number of liberal scholars who have become convinced of early dates based on the evidence available. Two of the most notable are J.A.T. Robinson and Eta Linnemann.

Second, it is stated as a foregone conclusion that the authors’ names were added to the manuscripts later on — perhaps as late as the second century. The critics assume that the Gospels were written too late to have been by eyewitnesses. Mark is assumed to be the first Gospel and the date of 70 AD is assigned. The rest of the Gospels are thought to be at least 10 years later. Certainly, books written so late after the deaths of Jesus and the Apostles could not be by contemporary eyewitnesses of the events.

External testimony is routinely ignored. We have author attributions as early the extant fragments of Papias’ work, Expositions of the Oracles of the Lord, which according to C.E. Hill was written “as early as 110 and probably no later than the early 130s, with several scholars opting for the earlier end of the spectrum.” We also have Irenaeus’ statement (c. 180 AD) that Papias was “a hearer of John, and companion of Polycarp, a man of old time” (Against Heresies 5.33.4). If we take Irenaeus’ statement at face value, there is no reason to suppose that the Church fathers, who wrote between 96 to 115 AD, did not know the names of the authors of the four Gospels and Acts. Papias names Matthew as the author of a Hebrew Gospel according to Matthew, and Mark as the author of what was preached by Peter, the Gospel according to Mark.

If the Gospels were not written by those whose names appeared on the books by the early second century, there is little possibility that they could have had the influence they did in the early church. It is unlikely that such a falsification of authorship could have occurred intentionally or even unintentionally.

Likewise, my fictitious novels about Joseph Fitzgerald Kennedy (see part 1) and his followers might fool a few children and some illiterate hillbillies who have lived their entire lives cut off from written communication, But this was not the civilization of ancient Rome and the early church. Although not everyone could read and write, literacy was the norm for Rome’s citizens and Jewish men especially were highly literate and aware of their own history as a people. The Gospels, to the contrary to the story of Joseph Fitzgerald Kennedy, are historical accounts that may be corroborated with other works, such as the histories written by Suetonius, Tacitus and Josephus. If they were not, they never could have risen to the level of acceptance as inspired and canonical writings recognized as scripture by the end of the first century.

There are two remarkable early examples of New Testament writings being quoted as scripture. The first is 1 Clement 13.8, which has the phrase, “the words of the Lord Jesus,” prior to a quote from the Gospels. Before and after this Gospel quotation, The Epistle of Clement (c. 96 AD) appeals to the authority of Old Testament scripture prefaced with the phrases, “for the Holy Spirit says” and “For the holy word says.” In 1 Clement 22.1, Christ is the source of the words of Psalm 34:11-17 and 2:10, “Christ calls us through his Holy Spirit.” It has been argued by some scholars that the use of the phrase “the words of the Lord Jesus” in chapter 13 indicates scriptural authority for the simple reason that Clement cites Jesus as the speaker of the Psalms in chapter 22.

The other example is Ignatius (c. 117 AD) who was the first Church Father to use many more quotations from the New Testament than from the Old Testament in his writings. Ignatius rebukes those who doubt the authority of the Gospel in his Epistle to the Philadelphians. In chapter 8, Ignatius plainly states that whenever he speaks the words of the Gospel with the phrase, “it is written,” then the Gospel has the same authority as Old Testament scripture. In the same passage, he likens those who would reject the authority of the Gospel by directly quoting the words of Jesus to the Apostle Paul in Acts 9:6, “It is hard to kick against the pricks.” This demonstrates the acceptance of Luke and Acts as scripture by Ignatius.

When was the New Testament written?

No matter your theological disposition, liberal or conservative, the dating of several New Testament papyri in the second century establishes that there is early and late window for the writing of the New Testament. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, thousands of manuscript fragments discovered by the renowned archaeologists, Grenfell and Hunt, in Egypt in the 1890s, yielded over 100 New Testament fragments that were older than any manuscripts that had been preserved up to that point.

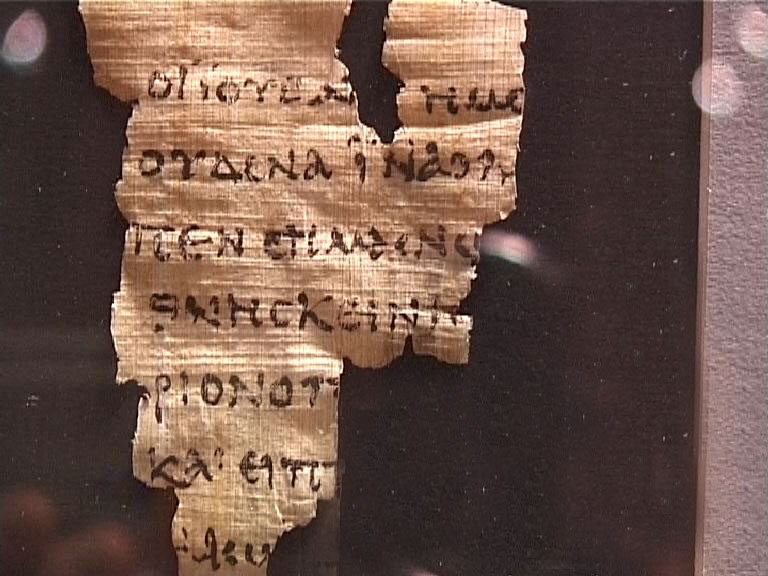

Facsimile of P52, the oldest known surviving Gospel fragment, c. 115 AD

The most startling discovery was a small scrap of papyrus called P52 that contains a portion of the Gospel of John. The consensus among paleographers is that the handwriting is circa 115 AD – also incidentally the approximate date of Papias’ Exposition. Since John was likely written in Asia Minor and P52 was found in Egypt, this fragment is likely at least a copy of a copy. This also indicates a wide distribution of copies of John at an early date.

Given the events of Acts, which end abruptly in about 60 AD, the earliest possible date for Acts is about 60 AD. In the world of critical literature and especially on the Internet, we still find people claiming a date as late as 130 AD for Luke. However, it should be obvious that a book could not have been written later than its earliest copy. Due to the almost universally accepted fact that the three synoptic Gospels were written prior to John, and since John was surely written prior to end of the first century, the three synoptic Gospels must have been completed prior to 90 AD.

That’s a 30 year window – 60 to 90 AD. That means if the Gospel of Luke was composed, according to the liberal dating, by 85 AD, the book of Acts would have been written soon after that date. In light of the point I made with the fictitious story of JFK, the date of 85 AD by an anonymous or pseudonymous author is impossible. To have gained acceptance among Christians at the beginning of the second century, the authenticity and historical reliability of both of these works would need to be airtight.

Numerous quotes from Luke, Acts, the other three Gospels and most other New Testament books appeared in the works of Clement, Ignatius, Polycarp, Papias and the writer of the Didache just a few years later. These men lived from the mid-first century onward and wrote their books from 96 to 115 AD. To quote Irenaeus, these writings of the church fathers were composed by men “who had seen and conversed with the apostles, while their preaching was still sounding in [their] ears, and their tradition was still before [their] eyes. Nor were they alone in this, for many who had been taught by the apostles still survived.”

Again, we are presented with the inevitable scenario in which the four written Gospels must have been composed and transmitted among a tight knit community that had some still living who had known and heard the Apostles preach.

Of course, one could make the charge that the letters of Clement, Ignatius and Polycarp are not genuine either and therefore are no witness to New Testament reliability. The problem with this hypothesis is that these books are accepted even by liberals as being completely authentic and genuine — the simple reason being that the church fathers of the late second century quote from them as well. There is a living link of flesh and blood from generation to generation. The Apostles who were with Jesus passed on their writings to the early bishops who transmitted them to their successors. After 96 AD, the supposed date for the Epistle of Clement, there is hardly a decade in which we don’t have a record, a witness, a writing of some type that confirms an earlier record, witness or writing. The New Testament has an incredibly strong pedigree in this regard.

What is meant by “anonymous” Gospels?

There are some accomplished scholars who dispute the authenticity of the Gospels. Bart Ehrman is a world-renowned New Testament scholar. In a brief Internet conversation with Ehrman earlier this year, I asked him about his insistence on Gospel anonymity. He gave his answer:

By definition (is this really a speculation? I thought it was a truism), a writing whose author does not identify him/herself is anonymous…. The authors of the Gospels of the New Testament (unlike other Gospels outside the New Testament, and unlike other books in the New Testament) do not indicate their identity. These books are therefore anonymous. If you want to identify the authors with one person or another, that’s fine – and you may have historical grounds. But in doing so you are attributing a book to someone, not indicating what the book itself says about its author.

Ehrman therefore insists that any writing in which an author does not identify himself by name within the text itself is by definition “anonymous.” However, there is absolutely no reason to think that the four Gospel authors’ names were not known or that they were not part of the titles of the books. Everyone knew who wrote The Annals in ancient times, but Tacitus did not put his name within the text. The Annals is not by definition “anonymous.” Consider also that there were four Gospels, each being copied hundreds of times, all the copies going in hundreds of different geographical directions, all ending up thousands of miles apart, yet each called by the same names no matter where they ended up decades later. The logical explanation for this is that before they were distributed throughout the known world, the titles and author names were affixed to them in some way.

I have no doubt that Bart Ehrman and other such critics are scholars and gentlemen. However, to conservative Christians, who have studied the Bible and then hear the speculations of liberal critics, they seem to us as complete idiots. As Paul says: “They profess to be wise, when really, they have become fools. They have been turned over to a reprobate mind.” I am reminded of the proverbial 800 pound gorilla in the room that the skeptic does not want to see.

4 Comments

Thanks for commenting! There are a few articles by Linnemann on the internet. One is here where she gives her testimony:

Linnemann's testimony

She was a student of Rudolph Bultmann who is one of the fathers of neo-orthodox theology. She was a prodigy whose first book on textual criticism was published shortly after she graduated and became a bestseller. She got swept into the higher critical pantheon of German scholars and was a respected icon among liberals for many years.

Many of her later writings are ignored or ridiculed by liberals because she boils everything down into the most simplistic terms for the layman. She presents the data and then her conclusions but doesn't waste a lot of time explaining how she got there. But it is her ability to cut through extraneous nonsense that is irksome to liberals.

The Neo-orthodox are often scholars who mean well, and do accept the divinity of Jesus, but they think that since traditional views on textual and higher criticism don't line up with the dominant liberal consensus, they ought to just concede and work within those parameters. The problem with this is that dating, authorship and the integrity of the texts really do matter.

Linnemann's testimony is that although she had nagging misgivings with liberal bias toward the supernatural and authentic authorship, she went along with this until her faith chilled to a frozen state.

When she witnessed supernatural healings in a charismatic fellowship, the barrier between her acceptance of authentic authorship disappeared. She was converted both to Christ and to a conservative view of authorship and dating.

It's possible for a liberal like J.A.T. Robinson to affirm early dates. But then he is stuck in the conundrum of there having been Gospels recorded by eyewitnesses and Jesus' prediction of the destruction of Jerusalem even while denying the supernatural. Robinson is woefully inconsistent in holding two contradictory views at once.

"Liberal early dating" is therefore an oxymoron. Robinson is a liberal who was converted to a conservative view on dating. So is Linnemann, the difference being that her conversion to Christ (not just to conservative theology) sparked a faith in the supernatural claims of scripture as well.

In a nutshell, the denial of the metaphysical supernatural in the NT necessitates a late date. And in turn, the late dates are held to as evidence against authenticity so that the "Q" document becomes necessary and then studies into the content of "Q" are used to buttress a synoptic theory based on the presupposition of later dates.

But when we look for actual physical or testimonial evidence for Q, there is none. It is a phantom document based on a presupposition held by those who need a "proto-Gospel" to explain the sudden emergence of a Gospel tradition after 70 AD.

My view is that Matthew was THE proto-Gospel that was preached and memorized in Aramaic or Hebrew. It was rendered in written form in Hebrew about 37 to 40 AD when the first Apostles started preaching outside of Judea and Samaria. Then there were many versions of proto-Matthew preached in Greek and other local languages and dialects. In short, the Gospel of Matthew is basically THE Gospel spoken of in the NT.

Luke and Mark began essentially as versions of THE Gospel with added material that came from one or more eyewitnesses. Then the FINAL version of Matthew appeared sometime in the early 60s.

I am not dogmatic about authorship of Matthew, but I think internal evidence suggests that it was compiled at least in part by one of the 12 Apostles who had writing ability -- which would narrow down the field quite a bit. I am not against the idea of a "committee of editors" as one of the church fathers records as the method of the compostion of John's Gospel.

I am also not against the idea that there were early committees of bishops who took the available manuscripts and came up with a final recension that became archetype of what we have today, in fact, these archetypes could be after the deaths of the Apostles -- but not as late as the second century -- and they would have been done by the direct disciples of the Apostles.

The traditional view of authorship of Matthew coupled with evidence for an early date gives Matthean priority and authenticity a strong argument in its favor.

Luke's Gospel and Mark's Gospel were really written by Luke and Mark. I explain in the articles that if they were not, then it would be odd that every early manuscript and every church father agrees on this when authorship is mentioned.

Two of the biggest assumptions that many Christians make regarding the truth claims of Christianity is that, one, eyewitnesses wrote the four gospels. The problem is, however, that the majority of scholars today do not believe this is true. The second big assumption many Christians make is that it would have been impossible for whoever wrote these four books to have invented details in their books, especially in regards to the Empty Tomb and the Resurrection appearances, due to the fact that eyewitnesses to these events would have still been alive when the gospels were written and distributed.

But consider this, dear Reader: Most scholars date the writing of the first gospel, Mark, as circa 70 AD. Who of the eyewitnesses to the death of Jesus and the alleged events after his death were still alive in 70 AD? That is four decades after Jesus’ death. During that time period, tens of thousands of people living in Palestine were killed in the Jewish-Roman wars of the mid and late 60’s, culminating in the destruction of Jerusalem.

How do we know that any eyewitness to the death of Jesus in circa 30 AD was still alive when the first gospel was written and distributed in circa 70 AD? How do we know that any eyewitness to the death of Jesus ever had the opportunity to read the Gospel of Mark and proof read it for accuracy?

I challenge Christians to list the name of even ONE eyewitness to the death of Jesus who was still alive in 70 AD along with the evidence to support your claim.

If you can’t list any names, dear Christian, how can you be sure that details such as the Empty Tomb, the detailed resurrection appearances, and the Ascension ever really occurred? How can you be sure that these details were not simply theological hyperbole…or…the exaggerations and embellishments of superstitious, first century, mostly uneducated people, who had retold these stories thousands of times, between thousands of people, from one language to another, from one country to another, over a period of many decades?