The following is an excerpt from the script of a video to be produced in the future, Christ’s Victorious Kingdom: Postmillinnialism Rediscovered. Some of the following has been edited from the writings of my friends, Bob and Rose Weiner.

The Immeasurable Power of the Gospel

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat

Of peace on earth, good will to men.And in despair I bowed my head,

“There is no peace on earth,” I said,

“For hate is strong and mocks the song

Of peace on earth, goodwill to men.”Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth he sleep,

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail

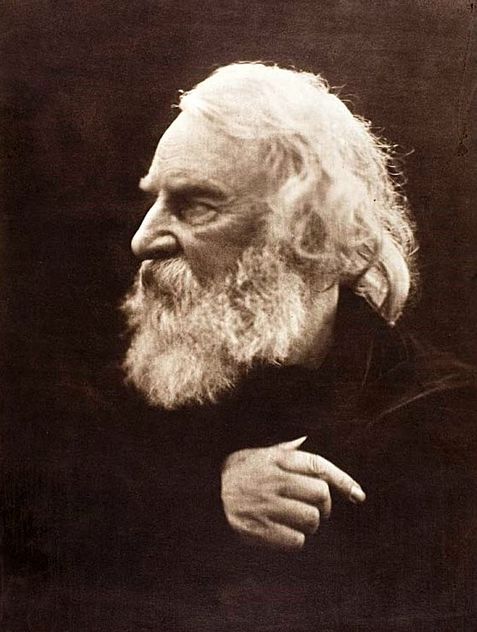

With peace on earth good will to men.”— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

“I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” December 25th, 1864

The U.S. Civil War was still raging when Longfellow wrote these words. Over 600,000 died, more than half due to disease and primitive medical care. He had just received news that his son, Charles Appleton Longfellow, had suffered crippling wounds as a soldier in battle. Just two years earlier, he had lost his wife to an accident with fire. Sitting down at his desk that Christmas Day, he heard church bells ringing. It was in this setting that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a committed Christian, wrote these lines.

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth he sleep,

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail

With peace on earth good will to men.”

While it might have looked as though the apocalypse was at the doorstep of his nation, Longfellow quoted scripture and persisted in what was known in early America as the “Puritan Hope” – that the Gospel was strong enough, not only to convert souls, but also to transform the nations bringing “peace on earth.”

The historic belief of the Church that the Gospel is destined to overcome all opposition is totally opposite of the ideas of the end-times that have been propagated throughout evangelical Christendom over the last century. The presence of evil in the world and sin in our nation has been viewed by modern Christians as an indication that civilization is crumbling, and that we Christians on that “sinking ship” should spend as much time as possible trying to rescue as many of the passengers as we can. This has resulted in an escape-orientated Christianity rather than dominion-oriented Christianity.

As David Chilton wrote in Paradise Restored:

Regardless of their numerous individual differences, the various defeatist schools of thought are solidly lined up together on one major point: The gospel of Jesus Christ will fail. Christianity will not be successful in its worldwide task. Christ’s Great Commission to disciple the nations will not be carried out. Satan and the forces of Antichrist will prevail. Jesus returns at the last moment, like the cavalry in B-grade westerns, to rescue the ragged little band of survivors.

As a result of almost a century of this type of teaching, the Church has lost many major battles to the enemy. The Gospel is just as powerful today as it was in the days of the Reformation and the two Great Awakenings in America. It is not the Gospel that has changed; it is the orientation of the Christian that has made the difference.

Therefore, some questions we ought ask ourselves.

Do I have an eschatology of defeat or an eschatology of victory?

Do I see the devil running the world and getting more and more powerful all the time?

Do I see the ministry of the church as mainly that of a rescue mission, with no other lasting effect in the world other than saving a few individuals from hell?

Is my message for the “last days” simply: “Antichrist is coming, run to the wilderness”?

- or -

Does the Gospel center on a powerful vision that sees Christianity becoming victorious throughout the entire world before the second coming of Christ?

Such a worldview was completely foreign to many of the great Christian scholars of past centuries. On the contrary, the view of the Church in history was held by such godly and respected men as throughout history, such as, Athanasius, Augustine, Eusebius, John Calvin, John Owen, Jonathan Edwards, Charles Hodge, Robert L. Dabney and Benjamin Warfield to name just a few.

This ought to tell us that the postmillennial worldview is well worth considering.

your_ip_is_blacklisted_by sbl.spamhaus.org