Here we will briefly survey the power of Christ’s victorious kingdom in history by looking at the faith and teachings of great saints of old, from Athanasius and Augustine to Jonathan Edwards and Charles Hodge, to the revival of the Puritan Hope in our current day. We will see that an optimistic view of what the Holy Spirit can accomplish through the Church is not a strange, new minority belief, but in fact represents what much of the Church has believed throughout history.

At the outset, we should realize that the Word of God is supreme. Our eschatological view should be colored not so much by what is occurring in the present or by what has occurred in history – as by what the scriptures state. On the other hand, if the Word of God is true on the doctrine of the kingdom of God, then we should expect to see the advance of the kingdom in time and history just as Jesus predicted.

Then He said, “To what shall we liken the kingdom of God? Or with what parable shall we picture it? It is like a mustard seed which, when it is sown on the ground, is smaller than all the seeds on earth; but when it is sown, it grows up and becomes greater than all herbs, and shoots out large branches, so that the birds of the air may nest under its shade.” (Mark 4:30-32).

Why do so many Christian confidently insist that God the Father and God the Son can never fail in their appointed tasks, but seem to suggest that the Holy Spirit will fail in leading the Church to full maturity and in fulfilling the Great Commission?

There are organized Christian churches today in every geopolitical nation on earth – the dream of missionaries in past centuries. Yet this is taken for granted. If the current dispensationalist premillennial viewpoint is correct, then there is nothing left to that needs to happen. There is nothing to stop Jesus from catching us up in the sky, as the song goes, to “fly way” in “the by and by.”

In fact, it is the dispensationalist system – with its belief in the victory of evil over the Church at least until Christ returns – that is the theological novelty. If the historic eschatological viewpoint is correct, then we still have a big job to do. Our task isn’t merely to preach the Gospel to the whole world making some disciples from some nations, but to “make disciples of all nations, teaching them,” in the words of our Lord, “to obey all the things I have commanded you.”

It is also problematic that few modern Christians know much about the history of the Church or western civilization. Or worse, they have been brain-washed by the liberal modernist view that much of Christian history may be characterized as the “Dark Ages” – not understanding that this term was coined by Renaissance humanists to describe Christian civilization – which they hoped would be replaced by a new “enlightened” age in which the pagan culture of the Greeks and Romans would be revived.

Yet even to these humanist thinkers the destruction of pagan idolatry and the victory of Christianity over pagan culture was undeniable. Advances in archaeology in the past 150 years has shed much light on the Ancient Roman period and has offered a greater understanding of its positive developments during the Middle Ages.

What is even more remarkable is to read the accounts of Church Fathers such as Tertullian and Athanasius, who saw the brutal persecution of the Christian Church, and yet remained hopeful about the inevitable advance of the Gospel. They saw Christ conquering all idolatry and pagan error even in their own day.

The Roman Period

According to historian Kenneth Scott Latourette:

One of the most amazing and significant facts of history, is that within five centuries of its birth Christianity won the professed allegiance of the overwhelming majority of the population of the Roman Empire and even the support of the Roman state (Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity).

Latourette goes on to mention the main factors that led to Christian Dominion in the Roman Empire including:

- The conversion of Roman senators and emperors

- The disintegration of Roman society

- The Church’s organizational strength

- The adaptability of the Church toward cultural conditions

- The emphasis on intimacy with a personal God

- The Church’s high moral standards

All these factors led to a piqued interest in the new faith of this small yet growing sect of Christians in the Roman Empire.

Less well known today is that fact that the early Christians publicly demonstrated the ability to cast out demons.

Tertullian

Tertullian of Carthage is one of the many Church Fathers who spoke confidently to his pagan opponents about the spiritual power of Christ through believers to make incursions into the strongholds of demons – to “harrow hell” – as the title of this book maintains. Although premillennialist in his eschatology, Tertullian strongly proclaimed that the Church was destined to overcome every gate of hell.

Were it not for us, who would free you from those hidden foes that are ever making havoc of your health in soul and body – from those raids of the demons, I mean, which we repel from you without reward or hire? (Tertullian, 1 Apology 37).

Tertullian again claims power over the gates of hell in his address to the Roman magistrate Scapula.

We do more than repudiate the demons: we overcome them, we expose then daily to contempt, and exorcise them from their victims, as is well known to many people (Tertullian, Letter to Scapula 2).

Missions expert and Church historian C. Peter Wagner explained the result of such confidence in the power of the Gospel message.

Christian preachers in those days were so sure of the power of God that they did not hesitate to engage in power encounters. They would challenge in public the power of pagan gods with the power of Jesus…. All this involved the manhandling of demons – humiliating them, making them howl, beg for mercy, tell their secrets, and depart in a hurry. By the time the Christian preachers got through, no one would want to worship such nasty, lower powers. The supernatural power of God driving all competition from the field should be seen as the chief instrument of conversion in those first centuries (C. Peter Wagner, The Third Wave of the Holy Spirit).

Chiliasm vs. the Common Church Doctrine

We know there were Christians as early as the second century who rejected the doctrine of the premillennial return of Christ followed by an earthly, physical reign from Jerusalem for a literal one thousand years. This was known as chiliasm or millenarianism.

Justin Martyr of Rome, in his Dialogue with Trypho (chapters 80-81) asserts that that at the Second Coming, there will be a resurrection of the body and that the newly rebuilt and enlarged Jerusalem will last for one thousand years, but he adds “many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.”

The premillennialst view – though nothing like the dispensationalist version of today — was expounded upon by some early Church Fathers and Apologists in the Epistle of Barnabas, the writings of Irenaeus of Lyons, Hippolytus of Rome and Tertullian of Carthage. What we know today as amillennialism or postmillennialism did not yet have a name, but became simply the “Common Church Doctrine” after the time of Augustine.

The chiliast view was rejected partly because it was taught by heretics, such as the Cerinthians, the Ebionites and the Montanists. In fact, the first full exposition of the Book of Revelation was written as a partial futurist/partial preterist work by Victorinius of Pettau in the third century. He concludes his Commentary on the Apocalypse with the following condemnation of chiliasm.

Therefore, they are not to be heard who assure themselves that there is to be an earthly reign of a thousand years; who think, that is to say, with the heretic Cerinthus. For the kingdom of Christ is now eternal in the saints, although the glory of the saints shall be manifested after the resurrection.

This is thought by some to be a later addition, but it was certainly a contemporary idea of Victorinius’ time since Justin Martyr conceded such a view existed at least 100 years earlier.

Clement of Alexandria

Although Clement never stated a clear position on the nature of the millennium, he was probably a premillennialist like many other second century Christian writers. However, the foundation of the shift toward an amillennial/postmillennial view can be seen in his writings. Clement taught the Roman-Jewish War prosecuted by Nero and Vespasian was the fulfillment of the “abomination of desolation” prophesied in Daniel 9, 12 and Matthew 14. Some commentators, such as Victorinius of Pettau in the third century, extended this preterist paradigm to the book of Revelation as well. According to Victorinius’ Commentary on the Apocalypse, the kings of Revelation 17 were the Roman emperors. This led to the inevitable conclusion that the millennium described in Revelation 20-22 is symbolic of the kingdom of God – a time period stretching from the First Advent of Christ to the Second Advent.

Athanasius

We can see a pronounced eschatology of victory in the words of St. Athanasius, the great Church Father of the late third and fourth century whose classic book, On the Incarnation of the Word of God, reveals the Christian worldview of hope. He summarized its thesis:

Since the Savior came to dwell in our midst, not only does idolatry no longer increase, but it is getting less and gradually ceasing to be. Similarly, not only does the wisdom of the Greeks no longer make any progress, but that which used to be is disappearing. And demons, so far from continuing to impose on people by their deceits and oracle-givings and sorceries, are routed by the sign of the cross if they so much as try. On the other hand, while idolatry and everything else that opposes the faith of Christ is daily dwindling and weakening and falling, the Savior’s teaching is increasing everywhere! Worship, then, the Savior “Who is above all” and mighty, even God the Word, and condemn those who are being defeated and made to disappear by Him. When the sun has come, darkness prevails no longer; any of it that may be left anywhere is driven away. So also, now that the Divine epiphany of the Word of God has taken place, the darkness of idols prevails no more, and all parts of the world in every direction are enlightened by His teaching (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation).

Athanasius himself experienced persecution from pagans and was banished from the Empire three times by the Arian heretics who held sway with civil authorities. The phrase “Athanasius against the world” (Athanasius contra mundum) was coined to describe a person who will stand for the truth no matter the prevailing popular opinion and no matter the cost.

How could Athanasius be so optimistic about the state of affairs in the world?

If he was like many Christians of today, he would have been formulating theories on which Roman authority was the Beast of Revelation and devising complex end-times prophecy charts. Athanasius believed that darkness was being driven from the world by the Light of lights simply because it is the overcoming truth of the Word of God.

Athanasius saw in the Gospel not just the fact that we can be born-again and free from sin, but that all of Creation could be born-again. According to Athanasius creation and salvation were one and the same. He wrote in his preface:

We will begin, then, with the creation of the world and with God its Maker, for the first fact that you must grasp is this: the renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word Who made it in the beginning. There is thus no inconsistency between creation and salvation; for the One Father has employed the same Agent for both works, effecting the salvation of the world through the same Word Who made it at first (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation).

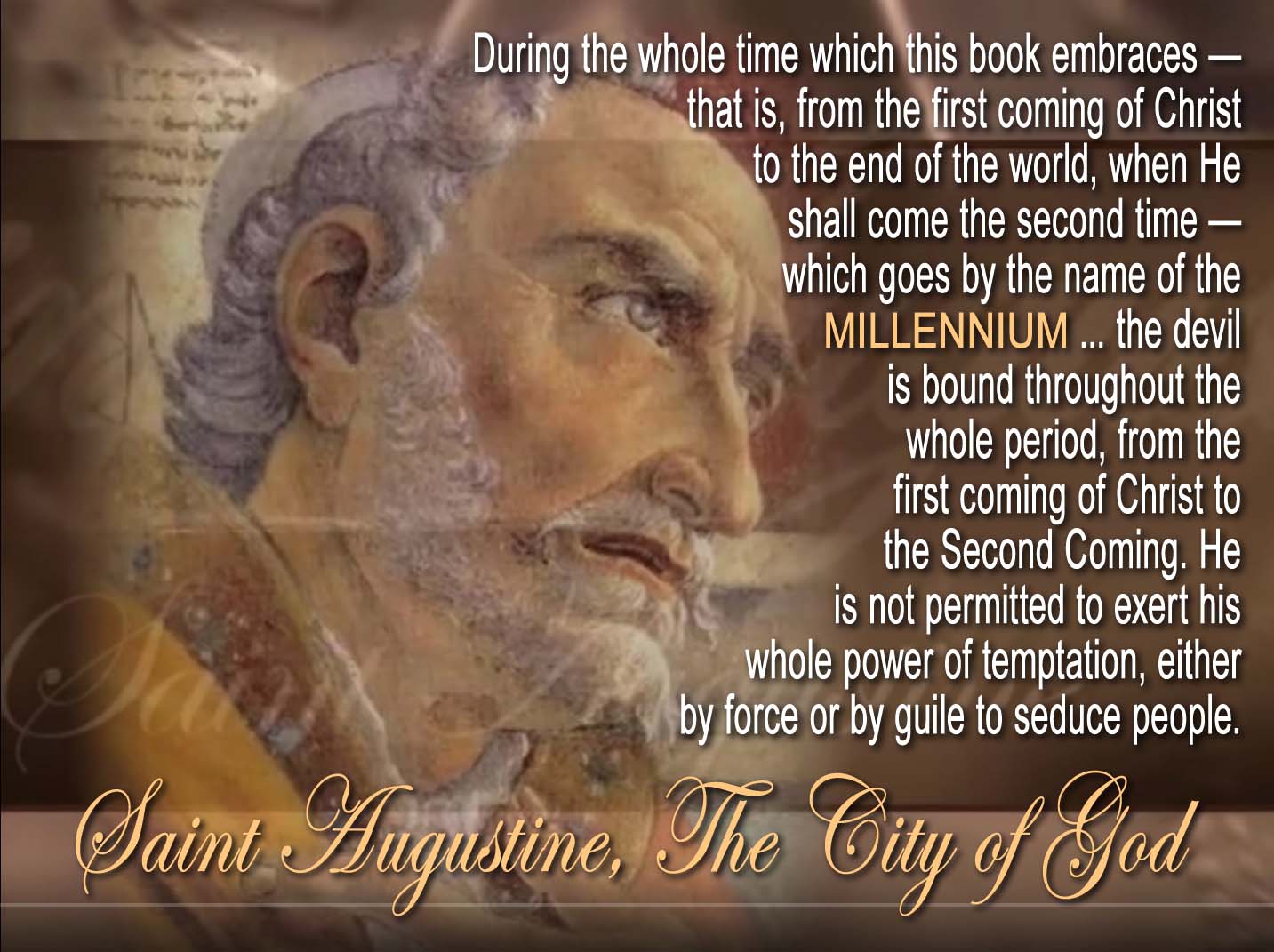

Augustine

However, Augustine of Hippo is responsible, more than any other Christian, for establishing the Common Church Doctrine that Christ is presently ruling and reigning over the nations while Satan is bound from deceiving the nations anymore. In his book, The City of God, Augustine viewed the Millennium of Revelation 20 not as a literal one thousand years in the far off future, but as

… the whole time which this book embraces – that is, from the first coming of Christ to the end of the world, when He shall come the second time … which goes by the name of a thousand years [Latin: mille anni or “millennium”]…

Augustine noted that the devil would be bound during this time.

The devil is bound throughout the whole period, from the first coming of Christ to the end of the world, which will be Christ’s second coming.

He noted that the Devil is largely incapable of seducing people away from Christ.

… he is not permitted to exert his whole power of temptation, either by force of by guile to seduce people (Augustine, The City of God).

Augustine is universally considered to be either an amillennialist – or perhaps more accurately, a postmillennialist – because of his understanding of the present reign of Christ in the Church age. But more importantly, Augustine’s eschatology solidified the eschatological Common Doctrine of the Church for over 1500 years afterward. Due to the influence of Augustine and others, such as Jerome, the premillennial view was almost unheard of in the Middle Ages.

The Middle Ages

The progress of kingdom growth was a mixed picture in the Middle Ages, but during a more than thousand year period, Christianity spread throughout much of the known world. British monks such as Saint Patrick (c. 389-461) brought the Gospel to Ireland. As a result, Celtic missionaries, such as Saint Columba, later established the Church in Scotland in the sixth century. By the seventh century, Christianity became the dominant religion in France through Columbanus. In the eighth century, Wilfred and Boniface did missionary work among the Germanic and Scandinavian tribes. In 988, Vladimir of Kiev was baptized and the whole Russian and Slavic world soon followed into membership in the Orthodox faith.

While there was an increasing worldliness noticeable in the Church during this period and Islam became equally widespread during this period, the Church also showed great vitality and remarkable abilities to adapt to the new cultures it encountered as it advanced throughout the western world.

The Age of Exploration, which began in the 1300s, brought Catholic missionaries to the New World and the Far East. Monastic orders, such as the Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians arose with the sole purpose of converting the world.

John Calvin

In the 1536 preface to the Institutes of the Christian Religion, the great reformer John Calvin explained to Francis I, king of France, that the Reformation would indeed triumph because it was empowered by Christ the king of the universe.

But our doctrine must stand, exalted above all the glory, and invincible by all the power of the world; because it is not ours, but the doctrine of the living God, and of his Christ, whom the Father hath constituted King, that he may have dominion from sea to sea, and from the river even to the ends of the earth, and that he may rule in such a manner, that the whole earth, with its strength of iron and with its splendor of gold and silver, smitten by the rod of his mouth, may be broken to pieces like a potter’s vessel; for thus do the prophets foretell the magnificence of his kingdom (Daniel 2:34; Isaiah 11:4; Psalm 2:9 conflated) (John Calvin, Preface to the 1536 edition, Institutes of the Christian Religion).

The Puritan Hope

Perhaps no other group expounded on the doctrine of postmillennialism as fully as many of the English and American Puritans and their numerous theological successors. For this reason, author and historian Iain H. Murray has called this phenomenon, “The Puritan Hope.”

Thomas Brightman

In 1609, Thomas Brightman published an optimistic commentary on of the book of Revelation. Even amidst present persecutions of Christians, he claimed that the scriptures promised of an era of triumph for the Church on earth. This era will be characterized by the con version of the Jews and the fullness of the Gentiles, of peace on earth, a revitalized Church, and Christ ruling the nations by His Word. Brightman urged the British people to support and bless the Jews. As a result less than 50 years later, Puritan civil ruler Oliver Cromwell lifted a 100 year banishment of Jews, which had been in effect since the time of Henry VIII, allowing them to return to England.

William Gouge

William Gouge, Presbyterian minister, and one of the leaders of the assembly who produced the Westminster Confession, published and wrote many postmillennial works including his own book, The Progress of Divine Providence in 1645.

There are more particular promises concerning a future glory of the Christian Church, set down by the prophets in the Old Testament, and by Christ and his disciples in the New, especially in the book of the Revelation, then we have either heard of or seen in our days to be ‘accomplished. The glorious city described, Rev. 21:10, is by many judicious divines taken for a type of a spiritual, glorious estate of the Church of Christ under the gospel yet to come, and that before his last coming to judgment…. But this is most certain, that there are yet better things to come than have been since the first calling of the gentiles. Among other better things to come, the recalling of the Jews is most clearly and plentifully foretold by the prophets (William Gouge, The Progress of Divine Providence).

The “glorious estate” of the Church prior to the Day of Judgment – an estate characterized by the calling and conversion of the Jews and the fullness of the Gentiles into one visible Church – is a recurring theme that runs throughout the writings of the Puritans.

The Savoy Declaration

It is significant that, immediately after the adoption of the Westminster Confession by the English Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians, the independents drew up their own confession, called the Savoy Declaration of 1658, in which they explicitly affirmed their postmillennial hope.

… we expect that in the latter days, Antichrist being destroyed, the Jews called, and the adversaries of the kingdom of his dear Son broken, the churches of Christ being enlarged and edified through a free and plentiful communication of light and grace, shall enjoy in this world a more quiet, peaceable, and glorious condition than they have enjoyed (Savoy Declaration, 26.5).

We should note that although this is a historicist view with the papal power depicted as “Antichrist,” the confession falls solidly within the bounds of a postmillennial hope that was prevalent among the Puritans and Separatists.

John Owen

The great Puritan preacher John Owen noted six scriptural promises that would eventually characterize the Church and the world during the present millennial reign of Christ.

God in his appointed time will bring forth the kingdom of the Lord Christ unto more glory and power than in former days, I presume you are persuaded. Whatever will be more, these six things are clearly promised:

- Fullness of peace unto the gospel and the professors thereof, Isaiah 11:6,7; 54:13, 33:20,21; Revelation. 21:25.

- Purity and beauty of ordinances and gospel worship, Revelation 11:2, 21:3.

- Multitudes of converts, many persons, yea, nations, Isaiah 9:7,8; 66:8, 49:18-22; Revelation 7:9.

- The full casting out and rejecting of all will-worship, and their attendant abominations, Revelation 11:2.

- Professed subjection of the nations throughout the whole world unto the Lord Christ, Dan. 2:44, 7:26,27; Isaiah 60: 6-9 – the kingdoms become the kingdoms of our Lord and his Christ, Revelation 11:15.

- A most glorious and dreadful breaking of all that rise in opposition unto him, Isaiah 60:12.

Now, in order to the bringing in of this his rule and kingdom, with its attendances, the Lord Christ goes forth, in the first place, to cast down the things that stand in his way, dashing his enemies “in pieces like a potter’s vessel” (John Owen, “The Advantage of the Kingdom of Christ in the Shaking of the Kingdoms of the World”).

After the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, there were new significant thrusts of missionary activity into uncharted regions of the world, namely, North and South America, Africa and Asia.

Postmillennialism in America’s history

This victorious view of the Church’s role in history emerged as the common doctrine of eschatology in early America. Many American Puritans can also be described as postmillennialists. In fact, the colonization of America was fueled by this Puritan hope.

In the 1600s, the Pilgrims and Puritans brought the Gospel to America with the stated goal, according to the Mayflower Compact.

For the glory of God and advancement of the Christian faith.

William Bradford Governor of Plymouth Colony wrote of the Pilgrims’ purpose in founding a new colony:

A great hope and inward zeal they had of laying some good foundation, or at least to make some way thereunto, for the propagation and advancing the gospel or the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work …

John Winthrop

John Winthrop, Governor of Massachusetts, wrote of his optimism for the spread of the Gospel in the New World in his famous sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity.” Winthrop penned these words while en route to the New World on board the ship the Arbella. Winthrop outlined the purposes of God for New England. He described a harmonious Christian community whose laws and government would logically proceed from a godly and purposeful arrangement.

We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies, when He shall make us a praise and glory, that men shall say of succeeding plantations, “the Lord make it like that of New England.” For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and byword throughout the world, we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God and all professors for God’s sake, we shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.

And to shut up this discourse with that exhortation of Moses, that faithful servant of the Lord in His last farewell to Israel (Deut. 30), “Beloved there is now set before us life and good, death and evil, in that we are commanded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another, to walk in His ways and to keep His commandments and His ordinance, and His laws, and the articles of our covenant with Him that we may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God my bless us in the land whither we go to possess it. But if our hearts shall turn away so that we will not obey, but shall be seduced and worship other Gods, our pleasures, our profits, and serve them, it is propounded unto us this day we shall surely perish out of the good land whither we pass over this vast sea to possess it. Therefore let us choose life, that we, and our seed, may live, and by obeying His voice, and cleaving to Him, for He is our life and our prosperity” (John Winthrop, A Model of Christian Charity).

Here we see that when the Puritans first came to America, they hoped to build a Christian society that would be copied the world over. They were not naive, however, and understood that a lessening of Christian influence over the years could lead them to be cursed rather than blessed of God. If they disobeyed, they would be cut off and God might raise another Christian civilization in their place. Thus they began the Puritan settlement with postmillennial optimism.

John Cotton

The Puritans did not come to New England merely to escape persecution, but to establish the kingdom of God. One of the most beloved churchmen of his day, John Cotton, taught that the “New Jerusalem” was being founded in the America. Cotton’s postmillennialism caused him to expect a transformation of the world before Jesus’ return. God would bring into being a

visible state of a new Jerusalem, which shall flourish many years upon Earth, before the end of the world (John Cotton).

However, by the end of the 17th century, the Puritan hope began to quell. Seeing the trend of a waning Calvinistic influence, some began to foresee a pessimistic end of the world. They saw the antichrist looming on the horizon. Like many of today’s premillennialists, they adopted an end-times view of gloom and doom.

Looking at the writings of the Puritans during this time period we see contrasting views. The “Jeremiad” was a sermon preached to nurture this gloomy view that the “final apostasy” had set in. Often the book of Revelation was cited to foster pessimistic expectations, especially the destruction of Babylon in Revelation 18.

Other Christians dissented and began to work for Revival and Reformation in colonial America. One view was forward-looking seeing a glorious revival of religion on the horizon if the people of God would just pray and obey. The other view was backward-looking lamenting that the glory of God had departed and chastising the sins of the people without giving much hope for redemption.

The optimists were found not just those among the Puritans, but also the Anglican Church, the Scottish Presbyterians, Reformed churches, and later Wesley’s Methodists. The Moravian Society, founded by Count Leopold von Zinzendorf, sent out missionaries who reached Virginia, the Virgin Islands, Greenland, Surinam, Georgia and South Africa.

The Great Awakening of the early 1700s – led by such luminaries as John Wesley, George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards – drove forward the Gospel seeing a huge portion of England and America converted. It is estimated that about one-third of Americans professed a conversion to Christ in the years of the Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s. These Christians believed that even in the darkest times, God could appear as a great light and restore His glory to both Church and society. The Revival of Christianity that occurred in America and England during the 1700s was fueled by this postmillennial optimism.

John Wesley

Wesley taught that the Revivals that saw millions swept to the kingdom of God in the 1700s, known as the First Great Awakening would transform society as well. Love, honesty, sobriety, chastity, prudence, generosity and health would flow from hearts transformed by the love of God. Changed people would change the world. Scriptural holiness would spread across the land (Mitchell Lewis, Wesley’s Eschatological Optimism).

In “The General Spread of the Gospel,” Wesley wrote:

Is it not then highly probable, that God will carry on his work in the same manner as he has begun? That he will carry it on, I cannot doubt; however Luther may affirm, that a revival of religion never lasts above a generation, — that is, thirty years; (whereas the present revival has already continued above fifty) or however prophets of evil may say, “All will be at an end when the first instruments are removed.” There will then, very probably, be a great shaking; but I cannot induce myself to think that God has wrought so glorious a work, to let it sink and die away in a few years. No: I trust, this is only the beginning of a far greater work; the dawn of “the latter day glory.”

“The latter day glory” spoken of here is the gradual Christianization of the world through these revivals. Wesley’s sermon on “The Sign of the Times.”

Consider, what are the times which we have reason to believe are now at hand? And how is it that all who are called Christians, do not discern the signs of these times? The times which we have reason to believe are at hand, (if they are not already begun) are what many pious men have termed, the time of “the latter-day glory;” — meaning the time wherein God would gloriously display his power and love, in the fulfillment of his gracious promise that “the knowledge of the Lord shall cover the earth, as the waters cover the sea.”

As was the prevailing view of his day, Wesley thought that the “thousand years” referred to a present reality.

What occurs from Revelation 20:11-22:5, manifestly follows the things related in the nineteenth chapter. The thousand years came between; whereas if they were past, neither the beginning nor the end of them would fall within this period. In a short time those who assert that they are now at hand will appear to have spoken the truth. Meantime let every man consider what kind of happiness he expects therein. The danger does not lie in maintaining that the thousand years are yet to come; but in interpreting them, whether past or to come, in a gross and carnal sense (Wesley, Notes on the New Testament).

In The Hope of the Gospel – An Introduction to Wesleyan Eschatology, Dr. Vic Reasoner explains that Wesley taught a relative perfection, not a sinless perfection, which led to Wesley’s concept of the millennium as

that period in human history when the human race reaches a maturity level exhibited by a greater fear of God and his commandments when sinful practices are considered vices and Christian character is a sought virtue. It will be a time when Christian love is demonstrated instead of war, and the worship of God creates an awareness of the holy. But it will not be a time of absolute perfection nor a utopia…. Wesley had views on both subjects which are implicit in his writings. What was implicit in Wesley was developed explicitly by Wesleyan theologians as Postmillennialism. This development was consistent with the foundation laid by Wesley.

George Whitefield

The Scriptures are so far from encouraging us to plead for a diminution of divine influence in these last days of the gospel that on the contrary, we are encouraged to expect, hope, long, and pray for larger and more extensive showers of divine influence than any former age hath ever yet experienced. For are we not therein taught to pray, “That we may be filled with the fulness of God,” and to wait for a glorious epoch, “when the earth shall be filed with the Knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the seas”? Do not all the saints on earth, and all the spirits of just men made perfect in heaven, nay, all the angels and archangels about the throne of the most high God, night and day, join in this united cry, Lord Jesus, thus let thy kingdom come.

The postmillennial hope of 18th century revivalists in England was identical with that of American Calvinists, such as Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennant and Samuel Davies. The two groups corresponded with one another and cooperated in promoting Revival. Yet none was more influential in promoting postmillennial optimism than Edwards.

Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards, considered by many to be America’s greatest theologian, was an ardent postmillennialist. His writings fully developed the implications of a millennial Golden Age. Edwards is best known for his role in the Great Awakening, which began as a revival in several churches along the Connecticut River Valley. Through his preaching, revivalistic fervor spread throughout the colonies. Evangelical zeal and postmillennial hope went hand and hand. Edwards’ preaching that the millennium would be realized in its fullest sense in America fueled societal reformation within the embryonic nation of America.

In his book, On the History of Redemption, Edwards theorized that the advance of the Gospel would someday spread to Africa and Asia. Edwards wrote:

There is a kind of veil now cast over the greater part of the world, which keeps them in darkness. But then this veil shall be destroyed, “And he will destroy in this mountain the face of the covering cast over all people, and the veil that is spread over all nations” (Isaiah 25:7). And then all countries and nations, even those that are now most ignorant, shall be full of light and knowledge. Great knowledge shall prevail everywhere. It may be hoped, that then many of the Negroes and Indians will be divines, and that excellent books will be published in Africa, in Ethiopia, in Tartary, and other now the most barbarous countries. And not only learned men, but others of more ordinary education, shall then be very knowing in religion, “The eyes of them that see, shall not be dim; and the ears of them that hear, shall hearken. The heart also of the rash shall understand knowledge” (Isaiah 32:3,4).

In the first half of the 1700s, when Edwards was writing, the Christian population of Africa and Asia was less than one percent. That Africa would be converted to the Gospel was unbelievably optimistic. I have been associated with successful Christian missions in Africa, India and Tatarstan (now part of Russia) just as Edwards predicted. I have personally encountered many thousands young people from these nations who were converted to Christ. They are entering the ministry, writing books and dedicating their lives to the conversion of the lost.

If Edwards prediction of an unheard-of outpouring of God’s Spirit among these nations is considered so matter-of-factly by us today, then we should also be encouraged to imagine what is yet to come in the future.

In all of Edwards’ writings and sermons, he portrayed all of human history as a progressive march towards victory for the kingdom of God. Edwards believed that revivals in the American colonies and England were but a forerunner of what would commence in centuries to come the ultimate glorious light of a Golden Age. He taught that history moves through a pulsation of seasons of revival and spiritual awakening; that there are times of retreat and advance; that the work of revival is carried out by what he termed “remarkable outpourings of the Spirit.”

Time after time, when religion seemed to be almost gone, and it was come to the last extremity, then God granted a revival, and sent some angel or prophet, or raised up some eminent person, to be an instrument of their reformation.

Edwards was the instrument of New England’s Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s. He insisted that there would be times of conflict, remissions and lulls between the sovereign outpourings of the Spirit. A decline in the spiritual and moral character of a Christian nation, according to Edwards, is to be interpreted as a preparation for an even greater outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Even secular historians agree that the postmillennial optimism of the First Great Awakening gave the American colonies the impetus to seek independence from England. Ingrained in the early American consciousness was the idea that our form of civil government would eventually mirror the Golden Age of Israel.

Hymns of the Church

Perhaps nowhere else is the Puritan Hope so wonderfully expressed as in the numerous hymns of the past, many of which are well known today.

And yet how many have understood the postmillennial theology ingrained in these spiritual songs?

Charles Wesley, the great Methodist hymn writer and brother of John Wesley, wrote in some of his most famous verses.

When He first the work begun,

small and feeble was His day:

Now the Word doth swiftly run,

now it wins its widening way:

More and more it spreads and grows,

ever mighty to prevail,

Sin’s strongholds it now o’erthrows,

shakes the trembling gates of hell.— Charles Wesley, “See How Great a Flame Aspires”

A similarly optimistic exhortation is contained in many other classic hymns.

Lift high His royal banner,

It must not suffer loss,

From victory unto victory,

His army shall he lead,

Till every foe it vanquished,

And Christ is Lord indeed.

Stand up, stand up for Jesus,

The strife will not be long;

This day the noise of battle,

The next, the victor’s song!— George Duffield, “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus”

In addition to these well-known hymns, perhaps no other songwriter has made such an impact on the world as Isaac Watts, whose hymnal was one of the most published books of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Jesus shall reign wherever the sun

Does his successive journeys run:

His kingdom spread from shore to shore,

‘Till moon shall wax and wane no more.

To Him shall endless prayer be made

And endless praises crown His head.

People and realms of every tongue,

Dwell on His love with sweetest song,

And infant voices shall proclaim

Their early blessing on His name.– Isaac Watts, “Jesus Shall Reign”

No more let sins and sorrows grow,

Nor thorns infest the ground.

He comes to make His blessings flow

Far as the curse is found!– Isaac Watts, “Joy to the World”

For lo! the days are hastening on,

By prophet bards foretold,

When with the ever-circling years

Comes round the Age of Gold;

When peace shall over all the earth

Its ancient splendors fling

And the whole world send back the song

Which now thee angels sing!”– Isaac Watts, “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear”

The Second Great Awakening

John Jefferson Davis noted in this book, Christ’s Victorious Kingdom, that the one factor that has caused so many theologians in our day to reconsider postmillennialism is that it was the dominant millennial understanding of the nineteenth century. Not only did it inform the thinking and interpretative study of the Bible, but it fueled the great social reforms of the 1800s.

This was the vision of the Second Great Awakening. Although this movement did not display the theological rigor and unity of the previous century’s First Great Awakening, some of the most far-reaching social changes that this country has ever experienced – from the abolition of slavery, advances in education and care for the mentally ill – came out of this spiritual awakening. In fact, historians are almost in unanimous agreement that all of the social reform movements of the 1800s had their roots in Christian revivals.

Now the great business of the Church is to reform the world, to put away every kind of sin. The Church of Christ was originally organized to be a body of reformers … the Christian Church was designed to make aggressive movements in every direction – to lift up her voice and put forth her energies against iniquity in high and low places – to reform individuals, communities, and governments, and never rest until the kingdom and the greatness of the kingdom under the whole heaven shall be given to the people of the saints of the Most High God – until every form of iniquity be driven from the earth (Charles G. Finney, Systematic Theology).

In the 1800s, most school history textbooks stressed the idea of progress, that the world was improving due to advances in learning. Most Christians believed this was due to the advancement of the Gospel. As more and more people were converted to Christ, individual lives would reform and the world would become a better place.

The Age of Protestant Missions

William Carey founded the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792 with the purpose of bringing the Gospel to India. Carey is remembered for his famous quote regarding missions:

Expect great things from God, attempt great things for God (William Carey, Baptist Missionary Society).

Several other missionary societies were founded in England and America in the early 1800s. J. Hudson Taylor founded the Inland China Mission, the first “faith ministry” independent of denominational control that subsisted entirely on independent donations. The “mustard seed” of the Gospel, so small in the beginning, began to finally come to maturity and truly become a home for all the birds of the air – the Church became a house of prayer for all nations.

As David Livingstone, missionary to Africa preached:

Missionaries do not live before their time. Their great idea of converting the world to Christ is no chimera: it is divine. Christianity will triumph. It is equal to all it has to perform (David Livingstone).

19th Century Reformed Theologians

It is also notable that the greatest theologians of the 19th century were fueled in their study of Scripture by a postmillennial hope. Literally, volumes could be filled with the optimistic quotes of these great men concerning the advancement of the kingdom of God.

C.H. Spurgeon

The “prince of preachers,“ Charles Haddon Spurgeon, was at various times in his ministry, either a classic premillennialist or a postmillennialist. However, Spurgeon always proclaimed an optimistic outlook.

I myself believe that King Jesus will reign, and the idols be utterly abolished: but I expect the same power which once turned the world upside down will still continue to do it. The Holy Ghost would never suffer the imputation to rest upon His holy name that he was not able to convert the world (Charles Spurgeon).

Charles Hodge

As therefore the Scriptures teach that the kingdom of Christ is to extend over all the earth; that all nations are to serve Him; and that all people shall call Him blessed; it is to be inferred that these predictions refer to a state of things which is to exist before the second coming of Christ. This state is described as one of spiritual prosperity; God will pour out His Spirit upon all flesh; knowledge shall everywhere abound; wars shall cease to the ends of the earth … This does not imply that there is to be neither sin nor sorrow in the world during this long period, or that all men are to be true Christians. The tares are to grow together with the wheat until the harvest. The means of grace will still be needed; conversion and sanctification will be then what they ever have been (Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology).

B.B. Warfield

Benjamin Breckenridge Warfield stated that the world is indeed getting better, not worse.

… precisely what the risen Lord, who has been made head over all things for his church, is doing through these years that stretch between his first and second comings, is conquering the world to himself; and the world is to be nothing less than a converted world…. All conflict, then, will be over, the conquest of the world will be complete, before Jesus returns to earth.

1 Comment

Beautifully done. Like evolution, I look forward to the coming time when Schofieldism, too, will fade into a distant memory.