The hero of the Scotch Reformation, though four years older than Calvin, sat humbly at his feet and became more Calvinistic than Calvin. John Knox spent the five years of his exile (1554-1559), during the reign of Bloody Mary, mostly at Geneva, and found there “the most perfect school of Christ that ever was since the days of the Apostles.” After that model he led the Scotch people, with dauntless courage and energy, from mediaeval semi-barbarism into the light of modern civilization, and acquired a name which, next to those of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, is the greatest in the history of the Protestant Reformation (Philip Schaff).

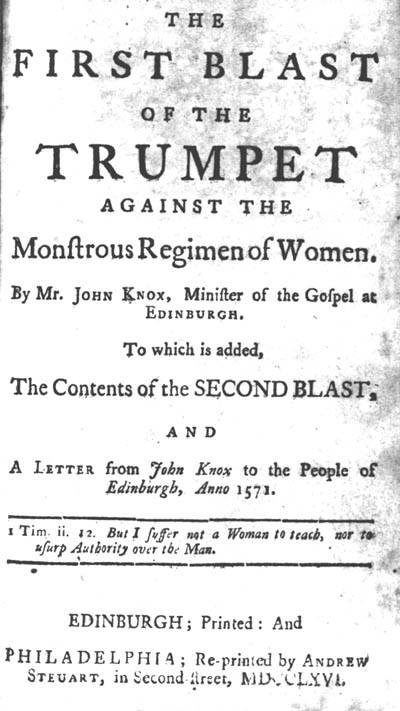

Part 2: What is The First Blast about?

Essentially, John Knox’s The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women is a polemic. It attacks female monarchs, arguing that civil rule by women is contrary to both nature and the Bible. A polemic is meant to stir controversy and get others to think through and argue an issue they would rather accommodate or sweep under the rug. There is a time for tactful wisdom and tender love when dealing with Christians who have erred. But there is also a time to attack aggressively, because it is the only course that is left when compassion and understanding have failed to curb abuse and error. Irenaeus, Tertullian and Martin Luther were just a few of the most notorious Christian polemicists in confronting heresy. This tactic is often misunderstood by today’s Christians.

Sections

The Preface – Knox begins in the very first sentence by calling Mary of Guise (pronounced “geese”) and Mary Tudor (known as “Bloody Mary” to Protestants) by the name of “Jezebel,” who had either murdered or driven the most Godly and zealous preachers from Scotland and England into exile, thus evoking Elijah’s plight (1 Kings 19). He then gives a litany of prophets and apostles of the Bible who did not shrink back from confronting both the sin of God’s people and the paganism of oppressor kings. He writes that God has ordained him as a watchman on the wall as he intends to speak out against a serious error even though he understood it to be “difficult and dangerous.”

Indeed, under the reigns of the Marys, hundreds of Knox’s Protestant friends, including women and children, had been burned at the stake as heretics. He ends the preface by saying he intends to write three times, twice anonymously, and the third time to take the blame and bring the wrath of the civil authorities on himself alone.

The First Blast: To Awake Women Degenerate – Knox then spends no more than one page arguing from “nature,” meaning that not only does God’s Word forbid women rulers, but nature itself speaks against it, as seen in the writings of the Greeks and Romans. He quotes a few short snippets from Aristotle and Roman law books. It is important to note (as I’ll explain in part 3) that Knox quotes a few short selections from pagan authors. He says that to argue from nature is “not the most sure foundation,” but “that men illuminated only by the light of nature have seen and have determined that it is a thing most repugnant to nature that women rule and govern over men.” Then for the rest of the tract, he argues exclusively from “revealed will and perfect ordinance of God,” that is, the Word of God.

In Knox’s biblical argument, he cites the commonly used scriptures that show women should not rule over men (1 Corinthians 11; Genesis 3; 1 Timothy 2; 1 Corinthians 14). About one-third of the way through this section, he begins to cite the arguments of the Church Fathers – Tertullian, Augustine, Ambrose, John Chrysostom – along a similar vein. The effect is to strengthen the interpretation of the same scriptures he has just used in his argument. He concludes this part by saying, “I depend not upon the determinations of men, so think I my cause no weaker, albeit their authority be denied unto me; provided that God by his will revealed, and manifest word, stand plain and evident on my side.” So here again, he emphasizes the authority of the Word of God as supreme, not the traditions of men.

About halfway through the pamphlet in the space of about three pages, Knox begins to turn his attention to the reason why this “subversion of God’s order” has occurred in his day. First, he notes that rather than continue the Reformation, England chose to install a queen who reinstated Roman Catholicism. To Knox, this was nothing less than the judgment of God on a nation who had rejected Christ as king. “And yet can they not consider, that where a woman reigneth and Papists bear authority, that, there must needs Satan the president of the council.” The result was the imprisonment and bloodshed of many faithful saints who died for the testimony of Jesus. He then cites Deuteronomy 17, which gives the qualifications for a Godly king. Knox notes that the description excludes foreigners and women.

Knox says that in his Second Blast of the Trumpet, which he never published, he will deal with the problem of “strangers” or “foreign kings.” For now, he proceeds with the qualifications for civil magistrates. Joshua 1 and Deuteronomy 17 command the king or the chief magistrate (the executive office) to know and meditate on the Law of God day and night. Like all Calvinists of his day, Knox believed that although the ceremonial law need not be observed, the king was bound to observe the moral law. He also points to the historical custom of Israel and Judah, that when the kingly line of strict succession failed, they never saw fit to appoint female rulers. He makes several references to “Jezabel” (Jezebel) here as a woman who not only usurped men, but God himself.

Four Objections Answered – Knox then concludes the last third of his tract, or about 12 pages, with a point-by-point answer to three common objections heard in his day about making exceptions for women rulers: first, the example of the woman judge, Deborah, and the counselor to David, Huldah; second, the law made by Moses for the daughters of Zelophehad; third, the kingdoms of continental Europe since about the 1300s had approved numerous women among their ruling monarchs; fourth, the long established custom had given examples of some “good” queens and the official approval of Roman Catholic canon law.

Knox begins by answering that the descriptive passages of the Bible, that is the historical accounts, do not imply prescriptive laws of God. He considers the prohibition of women monarchs to be no less binding than the law that kings may not take more than one wife. The practice of the Israelites doesn’t imply God’s approval. In the case of Deborah, he notes she was a judge sitting in the gates of the city, but not a military judge. That is, she did not assume the authority to bear the sword. Knox considers her ability to rule as a judge to be the ministry of the Holy Spirit. Deborah and Huldah spoke prophecy over Israel. It was not illegitimate, but he sees it as an act of God’s sovereignty to make this choice and not in the purview of men to set women in power as monarchs.

The answer concerning Deborah dispels the misperception that Knox was speaking of women other than the ungodly queens of his day who persecuted God’s Church and usurped the authority of Godly men. Knox challenges those who would defend “our mischievous Marys” to give an example of how they ever showed mercy to the people from God or delivered them from tyranny and idolatry. His concern was not so much women rulers who were like Deborah, but those who were then ruling England and Scotland who were just like Jezebel.

The daughters of Zelophehad is a reference to Numbers 27, in which five sisters – Mahlah, Noa, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah – as they prepared to enter the Promised Land, raised the case of a woman’s right and obligation to inherit property in the absence of a male heir in the family. Apparently, Knox’s opponents thought this was a law that supported allowing the reign of monarchs to pass through a female when direct male heirs were non-existent. Knox shows that the law actually commanded that the women marry within their own tribe. This would preclude the practice of Mary of Guise and Mary Stuart who married foreign Roman Catholic kings from France and Spain. Thus the law actually fights against the case for justifying these two queens as reigning monarchs.

Knox concludes his answer to objections by saying that any custom, good example or Roman Catholic law accepting of women rulers ought to be refuted by the Word of God itself. This is important because, although Knox begins with some short examples of how women rulers are “repugnant to nature,” he proceeds on the basis of Scripture and concludes by saying that nothing can prevail against God and His Word.

Call to Action – Knox lays the blame for the current persecution at the feet of England, whose Christians refused to complete the reformation of their national church. By refusing to put off the cause of the idolatry and persecution sweeping through both nations, they had brought God’s curse upon themselves. Here he uses his strongest condemnation for Queen Mary Tudor of England, whom he calls “cursed Jezabel of England” and “that horrible monster Jezabel of England.” Knox does not mince words and calls out cowardice in the cause of overthrowing tyranny. He ends the tract as he began – arrayed in a prophetic mantle predicting that the fire of God’s Word would soon consume these tyrants.

But the fire of God’s word is already laid to those rotten props (I include the Pope’s law with the rest) and presently they burn, albeit we espy not the flame. When they are consumed (as shortly they will be, for stubble and dry timber cannot long endure the fire) that rotten wall, the usurped and unjust empire of women, shall fall by itself in despite of all men, to the destruction of so many as shall labor to uphold it. And therefore let all men be advertised, for THE TRUMPET HATH ONCE BLOWN.

Why was it controversial?

Knox laid the foundation for Christians to resist wicked rulers. The controversy among the Reformed leaders of his day was not whether woman should not rule over men. The common position among the Reformed was that they should not, but some allowed for the various exceptions that Knox addresses. The position that troubled Calvin in Geneva, some Lutherans in Germany, and a short time later, Queen Elizabeth and her bishops in the Church of England, was that Knox was calling on the Christian population of England and Scotland to overthrow a monarch.

Although it looks like The First Blast was hastily written and published after Knox’s second flight from the British Isles, the idea had long been simmering in his mind. When Knox first came to Geneva in 1554, he had already been arrested and set to hard labor, which had almost killed him. He had witnessed hundreds of Protestants unjustly executed by the tyrant Jezebel queens of England and Scotland.

Knox arrived at Calvin’s school with numerous questions about Calvin’s “Lesser Magistrate Doctrine,” which had been developed in his Institutes of the Christian Religion and was prominent in the Lutheran Magdeburg Confession of 1550. These were bold, new proposals that spoke of the right and duty of the people to oppose a tyrant, but had never been carried out. Calvin had just finished with the Michael Servetus affair in 1553. Much of the city was controlled by Calvin’s supporters, but a political group labeled the “Libertines” responded with an attempted coup against the government. This was the last great political challenge Calvin had to face in Geneva. Further, Geneva was a “city-state.” It is easy to see why Calvin might have been remiss in satisfying Knox’s insistence that the Institute’s theory of civil resistance could apply to all of England and Scotland.

A few months later, Knox returned secretly to Scotland to preach and also married his first wife, Marjory Bowes. He was soon condemned for preaching heresy and had to return to Geneva the following year. At this time, Knox wrote The First Blast and published it anonymously by 1558. Although Calvin agreed with Knox that a female monarch was a punishment from God for the sins of mankind, he fell short of recommending civil resistance and rebellion. Knox intended to publish The Second Blast that would outline the conditions for resistance to civil tyranny more fully, but then Mary Tudor the Queen of England died. Knox was able to return to Scotland and continue his teaching more directly, but Queen Elizabeth I did not allow him to pass through England. She is said to have been infuriated by Knox’s tract, but it is arguable that the call to insurrection was far more troubling to her than his view on woman monarchs.

Common misperceptions

The greatest misperception of Knox was that he hated women. It is important to remember the historical context. This was the writing of a man facing persecution similar to that of the early Christians under the Romans. It cannot be overstated that while Knox hoped and prayed for the overthrow of tyrant queens, he was patient and gentle with women, including later Mary Queen of Scots herself, and worked for his enemies’ conversion. His married life and personal behavior with respect to women is also evidence that he was not writing to belittle or lower the status of women in relation to men in general or in the Christian family.

Two other misperceptions are that several of his Protestant friends, including Calvin himself, rebuked him for writing such an “anti-woman” screed, and that Knox actually retracted The First Blast soon after Elizabeth I came to the throne.

Why is The First Blast important?

Back then – In nations influenced by the Presbyterians and Puritans, the Reformation led to a robust Christian social theory and brought the greatest political freedom the world has ever known. It was the beginning of the death of the concept known as the “Divine Right of Kings.” Knox successfully proved that when a monarch became a tyrant and continually opposed God’s Law, the people were required to overthrow him. His reasoning was that both the monarch and the people were in covenant with God. When the king opposed the spread of the Gospel, it was the duty of the Christian population to restore the nation to covenant keeping.

The question also arose at that time as to whether the king was both the head of the church and the civil government. Andrew Melville, who was Knox’s contemporary, continued the work of establishing Presbyterianism as the mode of church government. James VI Stuart, King of Scotland and later England, insisted that the king be supreme in all matters of church and civil government. Melville insisted that Christ was the only head of the Church.

Melville himself set forth the principle in words that have become famous. Melville was chosen as a leader of a delegation to bring to the protest of the Synod of Fife against royal encroachments on the Church of Scotland’s autonomy. James was not impressed. After the king had expressed his displeasure, Melville opposed the king to his face.

Sirrah, ye are God’s silly vassal; there are two kings and two kingdoms in Scotland: there is king James, the head of the commonwealth; and there is Christ Jesus, the king of the Church, whose subject James VI is, and of whose kingdom he is not a king, not a lord, not a head, but a member.

In the early 1600s, Lex, Rex, a highly influential book written by the Scottish Presbyterian minister, Samuel Rutherford, advocated limited government, constitutionalism in politics, and distinct realms of church and civil governments, but opposed religious toleration. This idea led to the English Civil War in the time of Oliver Cromwell and finally to the Glorious Revolution in 1688 when a constitutional monarchy was finally established.

Lex, Rex is also profound play on words. Prior to Rutherford, the supporters of King Charles I had maintained that “the king is the law” or Rex, Lex. Rutherford maintained that “the Law is king” or Lex, Rex. The Law that Rutherford had in mind was God’s Law. Therefore Christ, not man, is king. We are to be ruled by a system of civil government under God’s Law, not man. This is a uniquely Christian concept derived from a covenantal interpretation of the Bible.

Today – Let’s be clear about one historical fact. The United States of America was not merely founded a “Christian nation,” but the American Revolution of 1775 was birthed out of the Knoxian and Cromwellian revolutions of the 1500s and 1600s in Scotland and England. The founding of America had more to do with the Presbyterian and Puritan movements than any other influence. John Knox and Oliver Cromwell were America’s founding fathers. It would do us good to examine both the character of the men who led these movements and the doctrines they preached and fought for.

In conclusion, it is important not to misinterpret Knox’s First Blast work as an attack on women in isolation of its political purpose. We cannot read it through the tinge of a 21st century feminist or postmodernist lens. We should not shy back from its sharp language for fear of being politically incorrect. On the contrary, understanding the background and character of John Knox, as well as the full historical context and impact of The First Blast, is vitally important to the course of Christian social and political reformation today.

your_ip_is_blacklisted_by sbl.spamhaus.org