The following is “Part 1” of the preface of a soon to be published book, In the Days of These Kings: The Prophecy of Daniel in Preterist Perspective. In the book, I argue that people who are looking to find “end-times” prophecies in Daniel miss the purpose and context of the book, which was to point the Jews in captivity — under Babylonian, Persian, Ptolemaic, Seleucid and finally Roman rule — to the time when the Messiah would come into the world.

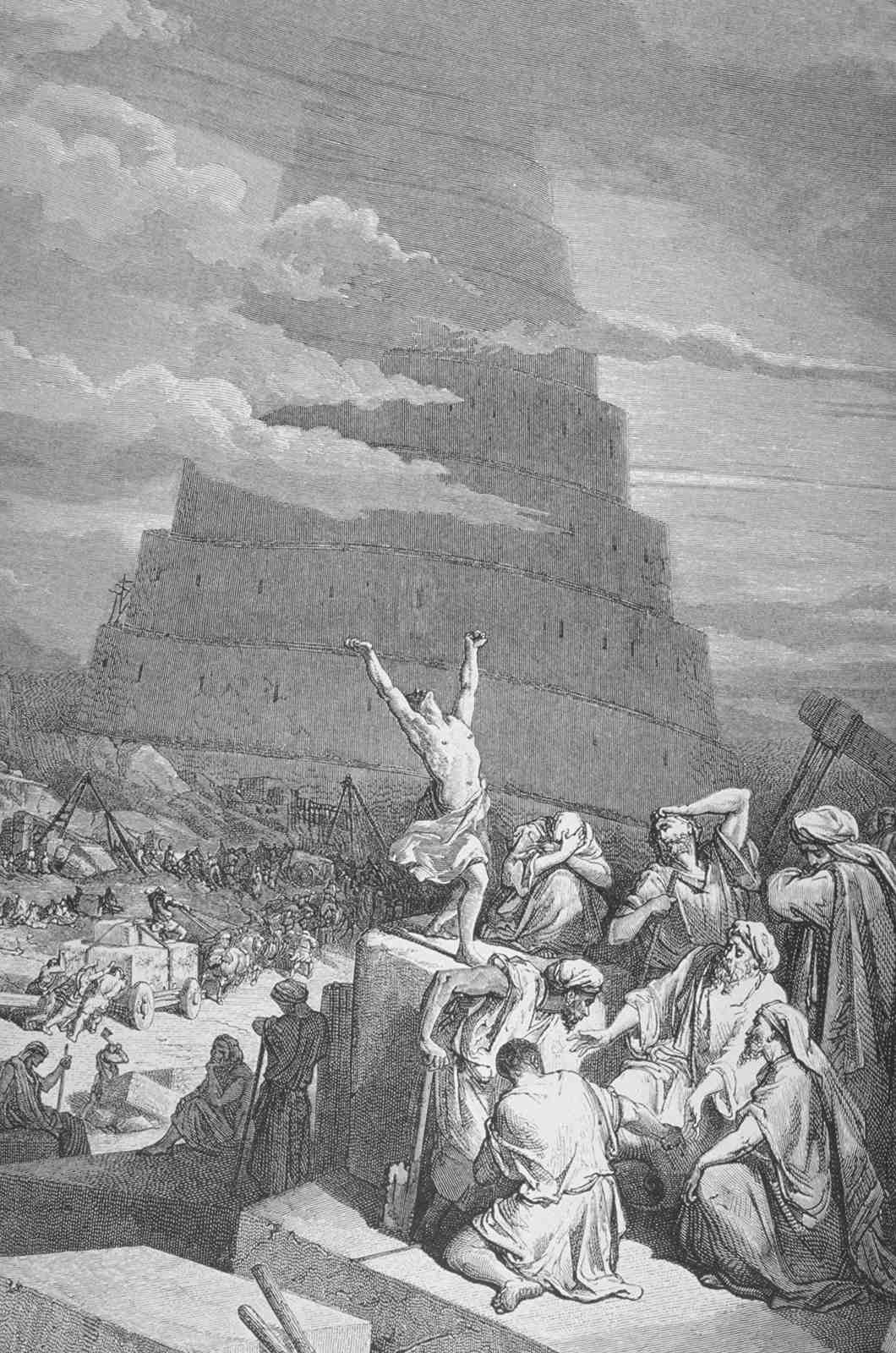

The Tower of Babel by Gustav Dore

There are stories told by the Jewish rabbis called midrashim (or midrash in the singular). These are interpretations and elaborations on biblical stories. They are meant to teach lessons and unlock applications of the story of God’s providence. One such story deals with Nimrod after the time of the Tower of Babel, who was a contemporary of Terah, the father of the Hebrew patriarch Abraham.

Nimrod was one of the sons of Kush [or Cush]. Kush was the son of Ham, the lowest and least important of Noah’s three sons. Nimrod came from a line which was cursed by Noah: “Cursed be Canaan, a slave of slaves shall he be unto his brothers.”

By birth, Nimrod had no right to be a king or ruler. But he was a mighty strong man, and sly and tricky, and a great hunter and trapper of men and animals. His followers grew in number, and soon Nimrod became the mighty king of Babylon, and his empire extended over other great cities.

As was to be expected, Nimrod did not feel very secure on his throne. He feared that one day there would appear a descendant of Noah’s heir and successor, Shem, and would claim the throne. He was determined to have no challenger. Some of Shem’s descendants had already been forced to leave that land and build their own cities and empires. There was only one prominent member of the Semitic family left in his country. He was Terah, the son of Nahor.

As you may have guessed by now, Terah, the father of Abraham is the center of conflict in this story. But in the midrash, Terah vows to be loyal to Nimrod after all the other descendants of Shem had left the region.

For although Nimrod had nothing to fear from Terah, he could not be sure if Terah’s sons would be as loyal to him as their father. Therefore, he was inwardly very pleased that his servant Terah had no children, and probably would never have any. But he could not be sure and Nimrod was not taking chances. He ordered his stargazers and astrologers to watch the sky for any sign of the appearance of a possible rival.

One night the star-gazers noticed a new star rising in the East. Every night it grew brighter. They informed Nimrod.

Nimrod called together his magicians and astrologers. They all agreed that it meant that a new baby was to be born who might challenge Nimrod’s power. It was decided that in order to prevent this, all new-born baby boys would have to die, starting from the king’s own palace, down to the humblest slave’s hut.

You may have wondered by now, “When was this written?” and noticed the similarities between the infancy stories of Moses and Jesus. Likely, the origin of this midrash is later than the first century. The rabbis created this story through the influence of Moses’ Exodus narrative and their familiarity with the nativity story in the Christian Gospel of Matthew.

For three years, little Abraham remained in the cave where he did not know day from night. Then he came out of the cave and saw the bright sun in the sky, and thought that it was G d, who had created the heaven and the earth, and him, too. But in the evening the sun went down, and the moon rose in the sky, surrounded by myriads of stars. “This must be G d,” Abraham decided. But the moon, too, disappeared, and the sun reappeared, and Abraham decided that there must be a G d Who rules over the sun and the moon and the stars, and the whole world. And so, from the age of three years and on, Abraham knew that there was only one G d, and he was resolved to pray to Him and worship Him alone (“Nimrod and Abraham, The Two Rivals,” Chabad.org).

In the Exodus narrative, the infant Moses is hidden among the bulrushes along the Nile River by his sister, Miriam, and grows up in the very shelter of Pharaoh’s court (Exodus 2:1-8). The Gospel According to Matthew tells of Jesus’ flight from Herod (Matthew 2:1-23). The Gospel According to Luke tells of his later appearance in the Temple as a wise child debating with the rabbis at the age of twelve (Luke 2:41-49). Likewise, in the midrash, Abraham is hidden in the wilderness in a cave for three years until he experienced a direct revelation of God as a wise young child of three.

I must stress at the outset that the midrashim are at best apocryphal stories meant to illustrate biblical truth. The midrashim are understood by the Jews to be neither inerrant truth, nor factual in detail. They were not meant to be thought of as authoritative, but as imaginative interpretations and instructive elaborations. The rabbis understood that they were weaving stories or romances. The early Christians had similar narratives, such as the Infancy Gospel of James, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Shepherd of Hermas and many others. At no time were they thought to have apostolic or prophetic authority, but were read for edification being illustrative of biblical truth, just as we would use Bible stories for young people or watch Bible-based films today for entertainment.

Of course, in the biblical story of Abraham, God calls for the sacrifice Isaac. Abraham is willing to comply, but Isaac is then rescued by an angel (Genesis 22:1-19). This too points to the Gospel revelation of the Father who gave His only begotten Son as a sacrifice for the sins of the world. The plan of God was to establish a covenantal inheritance through Abraham to the time of Christ. Isaac was a type or a foreshadowing of this promise.

It is important not to miss the point here. The truth illustrated in this particular midrash is powerful. We see it in pagan myths as well. Eternity is written on the hearts of those who are open to divine revelation through nature. Throughout history, pagans have often understood their fallen nature and need for salvation, but never the full truth of the Gospel that was revealed at the coming of Jesus Christ (Ecclesiastes 3:11; Romans 1:20).

Here in seminal form is the principle of spiritual warfare that runs like a scarlet thread throughout the Bible. It is the warfare of the seed of the serpent versus the seed of the woman in the curse that God put on the devil after the fall of man.

“And I will put enmity

Between you and the woman,

And between your seed and her Seed;

He shall bruise your head,

And you shall bruise His heel” (Genesis 3:15).

In pagan histories, we see man forever trying to be his own savior. The strong man always fails to bring salvation and instead births despotism and a worse type of bondage. Often he is overthrown by his own offspring or brothers. A young child is birthed in the shadow of a tyrant who desires world domination. The child grows up not only to usurp the evil king, but to grow in power far beyond that of the uneasy head that wears the crown.

This is the Oedipus myth in which the Greek king of Thebes received an oracle telling that his child would grow up to kill his father and marry his mother. In his fear and insecurity, the king hired a trusted servant to dispatch the child. The servant felt pity on the child and hid him in the wilderness. The child was found by a shepherd who then gave the child to another royal family. The child Oedipus came of age ignorant of his heritage and unknowingly fulfilled the prophecy precisely because of the paranoia of the father.

In the Roman culture, there is the story of Romulus and Remus who are abandoned by a king’s daughter, named Numitor.

Before their conception, Numitor’s brother Amulius had seized power, killed Numitor’s male heirs and forced Rhea Silvia to become a Vestal Virgin, sworn to chastity. Rhea Silvia conceives the twins by the god Mars. Once the twins are born, Amulius has them abandoned to die in the Tiber river. They are saved by a series of miraculous interventions: the river carries them to a place of safety, where a she-wolf finds and suckles them, and a woodpecker feeds them. A shepherd and his wife find them there, and fosters them to manhood as simple shepherds (“Romulus and Remus,” Wikipedia).

Upon assuming manhood, Romulus and Remus quarreled over the location of a city they hoped to found. Romulus slew Remus and founded the city of Rome on Palantine Hill. He gathered refugees and orphans, who were mostly unmarried men. He formed a Senate and an army and conquered the region. Eventually, this city-state dominated the world over the course of several centuries.

In pagan history, we find the battle of the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent in the legends surrounding various world conquerors. The grandfather of the Persian king, Cyrus the Great, was named Astyages.

According to Herodotus, Astyages had a dream about the son of his daughter Mandane and her husband Cambyses, [the child Cyrus], which he took as an evil omen. Therefore, Astyages ordered his courtier Harpagus to kill the young boy, but Harpagus secretly gave it to a herdsman, who was to do the dreadful deed. Fortunately, the herdsman and his wife decided not to kill the baby, but to accept him as their own son. When the boy was ten years old, it became obvious that he was not a herdsman’s son. His behavior was too noble, according to Herodotus. Astyages started to suspect what had happened when he interviewed the boy and noticed that his face resembled his own. Cyrus received favorable treatment and was allowed to go to his own parents, Cambyses and Mandane. When Cyrus had come of age … he organized a federation of ten Persian tribes and revolted. The united army of Medes and Persians marched to the Median capital and seized Astyages (“Astyages,” Livius.org).

Where does this common story come from? Is it Greek, Roman or Persian? Or does it come from a common source? This is also the story of King Arthur, Snow White and numerous other myths, folklore and fairy tales. The same thematic thread is woven through the origin legends many ancient cultures and differs only in the details. But these stories tell of a deeper truth. These are not myths in the sense that they are untrue.

Far from being a story that is not true, a myth is a story about truth. In fact the words, “myth” and “mythology” come from the Greek word mythos, meaning “word,” “tale” or “true narrative,” referring not only to the means by which it was transmitted, but also to its being rooted in truth. Mythos was also closely related to the word myo, meaning “to teach,” or “to initiate into the mysteries.” These stories are mythic in the true sense of the word. They reflect the spiritual beliefs, values and culture of the story tellers.

While I believe that most of these myths are fictional, there is a kernel of truth in each one. In some cases, they are remarkable yet factual pagan stories that are corroborated by ancient histories with verifiable details. History is sometimes stranger than fiction.

His Story in the Prophecy of Daniel

God has only one story – His story. The devil does not have any original stories. The pagan myths and legends are shadows of God’s history, which tells the truth about the nature of man and the plan of salvation.

We see the same themes repeated throughout the Bible. God always tells His story over and over again, each time giving layer upon layer of new truth to the story – “precept upon precept, line upon line” (Isaiah 28:13). The Jews were shown shadows and types of Christ throughout history, yet most still didn’t recognize Jesus. Of course, some of the Pharisees recognized that Jesus was claiming to be the divine Messiah, but they didn’t want to be under His authority. Jesus rebuked them for not understanding that the Scriptures testified of Him.

And the Father Himself, who sent Me, has testified of Me. You have neither heard His voice at any time, nor seen His form. But you do not have His word abiding in you, because whom He sent, Him you do not believe. You search the Scriptures, for in them you think you have eternal life; and these are they which testify of Me. But you are not willing to come to Me that you may have life (John 5:37-40).

To give another example, the story of Esther takes place in Persia during the Restoration period, while the Jews were in Judah rebuilding the city of Jerusalem. Xerxes, the king of Persia held a conference of all his noblemen throughout all his provinces. At a week-long feast, Queen Vashti fell out of favor by refusing to appear in the king’s court. As a consequence of her behavior, she was deposed. After King Xerxes conquered all of Asia Minor and parts of Macedonia and Greece, as prophesied in Daniel 11:2, he was finally defeated and forced to retreat. However, Xerxes still controlled all the Middle East and central Asia. He was for all intents and purposes the king of the world. He settled into a lifestyle of excess and multiplying the women of his harem. During this time, the province of Judah was destabilized. Although the Temple at Jerusalem had been rebuilt under Xerxes’ father, Darius the Great, the work on the restoration of the city had ceased. To make matters worse, the enemies of Judah sought to annihilate the Jewish people. By God’s providence, Xerxes took a second queen, a Jewess, who had been hidden in the foundation of the kingdom.

Each of the characters in Esther is related to the mythic war found in the seed of woman curse. Esther is a type of the woman who later births the Christ child. Xerxes is the king on the throne – a type of God the father. Haman represents the devil. Mordecai represents the intercession of the Holy Spirit in history. History shows us that the Jews not only averted a genocide at the hands of Haman, but also obtained divine favor from Xerxes and his son, Artaxerxes, who decreed the restoration of Jerusalem’s streets and walls. Although the name of God is not mentioned one time in the Book of Esther, it is a remarkable prophetic book expressing God’s “theater in the streets” that we call history.

Alexander the Great arose 150 years later in Macedonia. After his father Philip’s assassination in 336 BC, Alexander succeeded to the throne and inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. Later historians have argued that Alexander himself may have had a hand in the intrigue – or at least been privy to it. With his four generals, Seleucus, Ptolemy, Cassander and Lysimachus – he conquered the world – the Balkans, Asia Minor and the Persian Empire extending from Egypt to India.

As a boy, Alexander was trained by Aristotle. He was taught that there was one supreme god who was the prime cause of everything in the universe. Aristotle thought that there must be some eternal and imperishable substance, otherwise all substance would be perishable. He argued that this eternal actual substance must be the single prime mover. Although Aristotle’s god did not have a name, Alexander believed that this was Zeus, who ruled over a world of order and laws over all lesser gods, realms and kingdoms. Soon Alexander began to fashion himself the son of Heracles (Hercules) who himself was the son of Zeus. Numerous legends had Alexander being proclaimed as the son of a local god, whom Alexander interpreted as simply being the regional name for Zeus.

The Jewish historian Josephus even relates a legend explaining the reason why Alexander did not destroy the city of Jerusalem and the Temple, even though the Jews were earlier allied with the Persians. It is said that Alexander had a dream that he saw the High Priest of Jerusalem dressed in scarlet robes and the entire city dressed in white. When the High Priest met him at the gates with the whole city following him dressed in white, the color of peace, Alexander was led to the Temple where he offered sacrifice to the God of the Jews. Alexander was shown in the Daniel scroll where the “king of Greece” was prophesied to conquer the Persians. Alexander was so impressed that he spared the city and gave the Jews the same privileges they enjoyed under the Persians. This led to the Hellenization of Judea and a period of relative peace for the Jews under Ptolemaic and later Seleucid rule.

Could this legend of Alexander encountering his person in Daniel’s prophecy about the “king of Greece” be true? We are told by various sources that Alexander received a number of similar oracles. This began when he was a youth when the Oracle of Delphi told him he would conquer the world. After he conquered Alexandria, naming the city for himself, he received a prophecy from the Oracle at Siwa saying he was the son of the Egyptian god Amun. He began to believe he was truly a son of Zeus destined to conquer the world. He was encouraged to press into the East conquering the Persian Empire fighting at times against seemingly impossible odds.

Much like the men of Babel who sought to raise their tower to the heavens, and the Babylonians after them, Alexander finally settled in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace in Babylon and took a Persian wife named Roxanna, who bore him a child. He then indulged in a life of dissipation “having no more worlds left to conquer.” Accounts differ as to the cause of Alexander’s death, which came after a bout of drinking and a prolonged fever. His empire was divided up into four regions among Alexander’s generals called the Diadochi, or “successors.”

Pagan history was often used as a propaganda tool to keep tyrants on the throne. Augustus Caesar also had an “Oedipus Myth” ascribed to him that is recorded in Suetonius’ Lives of The Twelve Caesars.

According to Julius Marathus, a public portent warned the Roman people some months before Augustus’s birth that Nature was making ready to provide them with a king; and this caused the Senate such consternation that they issued a decree which forbade the rearing of any male child for a whole year. However, a group of senators whose wives were expectant prevented the decree from being filed at the Treasury and thus becoming law — for each of them hoped that the prophesied King would be his own son. (Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, “Augustus” 94, Robert Graves’ translation).

Octavian, later called by the name Julius Caesar Augustus, became the king of the world after defeating Marc Antony and having his adoptive father Julius Caesar’s only biological son, Caesarion, killed. But ironically the empire founded by Augustus was overshadowed by the King of kings, who was born among shepherds in Bethlehem.

The Meaning of History

Skeptics and the liberal critics can discount the supernatural in biblical stories – miraculous births and prophecies regarding the Son of God – but they cannot deny the “Golden Chain” of the Gospel story that runs through history. In the 20th century, the Marxists attempted to reinterpret history as a political struggle – a conflict between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie – inevitably leading to a communist worker’s paradise. In doing so, the communists have proposed their own secular eschatology. Prior to this revisionist materialist view history, there was a providential interpretation of history in many school textbooks, which was rooted in the Christian worldview.

I have spoken of the meaning of history. Surely it has a meaning, what else are we living for? Whichever way we turn in the material world we find things needful for our use and we think of them as God’s forethoughts, and as designed for our welfare. If there is design in the material world, there must be some meaning to history, some ultimate end to be accomplished (Charles Coffin, Old Times in the Colonies, p. 7).

Charles Coffin’s analysis of history was the norm in the 19th century and earlier. It stands in marked contrast to the materialist and Marxist view of history that has been taught ever since the early 20th century. But there are signs that this is changing.

We live in a postmodernist age. Postmodernism is an “anti-philosophical” worldview. It is the result of the willful death of humanist, rationalist, materialist and existentialist worldviews. The postmodernist concludes: “We can’t go any further without starting over. What is left? It’s all been done before and thought of before and we still have not secured our salvation.”

A large number of westerners now believe that the socialist policies of the last 100 years have led us only to the unfulfilled promises of a utopia. We have failed to create a perfect world in which human rights are extended to achieve total equality. No attempt at reforming inequality and unfairness using “politics as usual” seems to be working. Many see the political system as being rigged by the power brokers to benefit the elites. There is an urge toward deconstruction – a widely held cultural belief is that since the system is corrupt, it ought to be overthrown and demolished. However, nature abhors a vacuum. Little thought is given to whether the system that will replace it will be any better.

During the 2016 election cycle in America, I was surprised, but not shocked, to witness that for the first time in history, Americans saw fit to elect a commander-in-chief with no former political or military experience. The result of that voter rebellion against the norm will be for future historians to analyze, but the following synopsis (written by an anonymous friend) is appropriate.

Once “middle America” began to see the end result of humanism and materialism, many recoiled, yet felt helpless because the government institutions were already in place to make these philosophies turn into reality. So much seemed to happen so fast (although it was brewing for a very long time), and many wanted a strong man to undo the ravages of collectivism quickly.

The Kingdom of God is always advancing even when it is unnoticeable. However, it is exciting to live in a time when our sovereign Lord moves in a visible way. For example, the book of Hebrews was written at a time when God was about to remove one order, symbolized by the Temple at Jerusalem, and replace it with a kingdom that could not be shaken.

But now He has promised, saying, “Yet once more I shake not only the earth, but also heaven.” Now this, “Yet once more,” indicates the removal of those things that are being shaken, as of things that are made, that the things which cannot be shaken may remain.

Therefore, since we are receiving a kingdom which cannot be shaken, let us have grace, by which we may serve God acceptably with reverence and godly fear. For our God is a consuming fire (Hebrews 12:26-29).

This is why the prophecy of Daniel is applicable in our day. Understanding the redemptive-historical interpretation of the Bible brings an understanding of why God makes kingdoms rise and fall. His purpose is to prepare a people who will worship Him forever in reverence and awe.

your_ip_is_blacklisted_by sbl.spamhaus.org