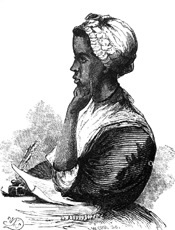

Born in 1753 in Africa, Phillis Wheatley was kidnapped and sold at a slave auction at age seven to a prosperous Boston family who educated her and treated her as a family member. Rescued from an otherwise hopeless situation by the sympathies of the Wheatley family, Phillis learned English with remarkable speed, and, although she never attended a formal school, she also learned Greek and Latin. It is clear that the Christian compassion of the Wheatley family was the nurturing womb in which Phillis’ rare gifts were cultivated. She came to know the Bible well; and three English poets Milton, Pope and Gray touched her deeply and exerted a strong influence on her verse.

She became a sensation in Boston in the 1760s when her poem on the death of the Reverend George Whitefield made her famous. Whitefield, the great evangelical preacher who frequently toured New England, was a close friend of Countess Selina of Huntington, and the latter invited Phillis to London to assist her in the publication of her poems.

Her literary gifts, intelligence, and piety were a striking example to her English and American audience of the triumph of human capacities over the circumstances of birth. The only hint of injustice found in any of her poems is in the line: “Some view our sable race with scornful eye.” It would be almost a hundred years before another black writer would drop the mask of convention and write openly about the African American experience.

Another theme, which runs like a scarlet thread throughout her poetry, is the salvation message of Christianity that all men and women, regardless of race or class, are in need of salvation. To the students at the University of Cambridge in New England (Harvard), she writes:

While an intrinsic ardor prompts to write,

The muses promise to assist my pen;

‘Twas not long since I left my native shore

The land of errors, and Egyptian gloom.

Father of mercy, ‘twas Thy gracious hand

Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you ‘tis given to scan the heights

Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

And mark the systems of revolving worlds.

Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

The blissful news by messengers from heav’n,

How Jesus blood for your redemption flows.

See Him with hands outstretched upon the cross;

Immense compassion in His bosom glows;

He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

When the whole human race by sin had fall’n,

He deigned to die that they might rise again,

And share with in the sublimest skies,

Life without death, and glory without end.

Improve your privileges while they stay,

Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

Or good or bad report of you to heav’n.

Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

By you be shunned, nor once remit your guard;

Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

An Ethiop tells you ‘tis your greatest foe;

Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

And immense perdition sinks the soul.

Phillis Wheatley received her freedom and married a free black man in 1778, but despite her skills was never able to support her family. Although she died in complete poverty, subsequent generations would pick up where she left off. Wheatley was the first black writer of consequence in America; and her life was an inspiring example to future generations of African Americans. In the 1830s, abolitionists reprinted her poetry and the powerful ideas contained in her deeply moving verse stood against the institution of slavery.

See also: Phillis Wheatley’s Complete Poems

your_ip_is_blacklisted_by sbl.spamhaus.org