Although I do not extensively comment on the historical passages of Daniel in chapters 1, 3-6, it is important to outline them at the outset. An understanding of the structure, composition and authorship of the Book of Daniel depends on the occasion and purpose of these historical chapters.

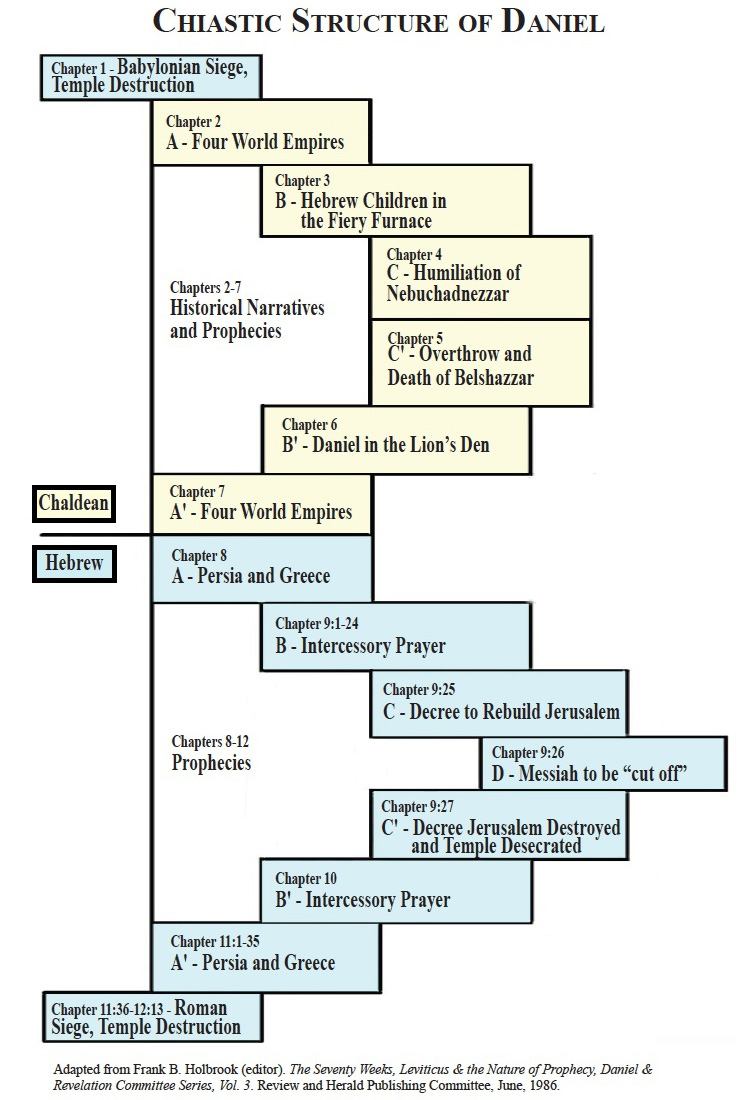

The two main sections of the book, Daniel 2-7 and 8-12, are organized in what is known as a chiasm or a chiastic structure. An example of chiastic structure would be two ideas, A and B, together with variants A′ and B′, presented as A, B, B′, A′ . To annotate chiasms, interpreters often use A′ to represent AA; B′ to represent BB; and so on.

First, concept A is mentioned once. Then B twice, A twice, etc., until the structure ends with a final A. The structure points to the contrast between two ideas. Scholars have known about this frequent occurrence of chiastic structure in the Bible for centuries, but it became a more popular study in the 1800s and the interest is only increasing. Bible scholars have found examples of chiastic structure in every book of the Bible, but some books are more known for this than others.

Genesis has more chiasms than any other book in the Bible. The beginning of Genesis 4, for example, uses the A, B, B′, A′ chiastic structure. The A, B, B′, A′ pattern emphasizes the contrast between the two sons of Adam, Abel and Cain. Genesis 4 describes their names, their occupations, and their offerings. Cain is mentioned first, then Abel twice, then Cain twice, and so on. The structure draws attention to the differences between Cain and Abel, pointing out the essential difference in their personalities.

A Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain, and said, “I have acquired a man from the Lord.”

B Then she bore again, this time his brother Abel.

BB Now Abel was a keeper of sheep,

AA but Cain was a tiller of the ground

A And in the process of time it came to pass that Cain brought an offering of the fruit of the ground to the Lord.

B Abel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat.

BB And the Lord respected Abel and his offering,

AA but He did not respect Cain and his offering. And Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell.

The major sections of the whole Book of Daniel are composed in a double-chiasm. The double chiastic structure is emphasized by the two languages in which the book is written: Aramaic and Hebrew.

The first chiasm is written in Aramaic from chapters 2-7 following an A, B, C, C′, B′, A′ pattern. Chapter 1 serves as an introduction. Then the dream and vision of chapters 2 and 7 form a recapitulation of two similar predictions of four world empires, A,A′. Daniel paints a vivid picture of four world empires being conquered by the kingdom of God with markedly different symbols representing each. In chapter 2, there are four types of metal making up a statue. In chapter 7, there are four types of beasts.

Chapters 3 and 6 also form a thematic or chiastic pair, B,B′. The casting of the three Hebrew children into the fiery furnace and their deliverance by “a fourth man walking in the midst of the fire, likened to the living Son of God” in chapter 3 is paired with the faith of the older Daniel shutting the mouths of the lions many years later in chapter 6.

Then chapters 4 and 5 also form a pair of ideas C,C′. The humiliation of King Nebuchadnezzar in chapter 4 is paired with the overthrow and death of his grandson Belshazzar in chapter 5.

The second chiasm is in Hebrew from chapters 8-12, also using the A, B, C, C′, B′, A′ pattern. The exception is that Daniel 9:26 is D, a break in the center of the pattern – A, B, C, D, C′, B′, A′.

Chapter 8 opens with Persia and Greece represented by a ram and a male goat. Persia is the empire that allows the Jews to rebuild the Temple. Greece is the empire divided into four kingdoms. Chapter 8 culminates with the tyranny of a “king of fierce countenance” who “shall destroy the mighty and holy people” and “stand up against the Prince of princes” (Daniel 8:23-25). This is paired with the line of Persian and Greek kings of chapter 11, which is centered around a “vile person” who sets up the “abomination of desolation” in the Temple, and continues into chapter 12 in which the Temple is desecrated once again, this time by the Romans in AD 70. Essentially, the Fifth Vision is a recapitulation of the Third Vision giving much more detail from the Second Kingdom of Cyrus to the time of the Fourth Kingdom of the Romans. The Third and Fifth Visions are the first pair in the chiasm, or A,A′.

The second pairing is the two intercessory prayers recorded in the opening of chapter 9:1-24 and chapter 10, or B,B′.

The third pairing is the decree to rebuild Jerusalem in Daniel 9:25 and the decree that Jerusalem is to be destroyed and the Temple desecrated in Daniel 9:27. This is C,C′.

At the very center of the C,C′ chiasm is one verse, 9:26, which is the Messiah being “cut-off” – the greatest event in history – the crucifixion of Jesus Christ for the sins of the nations of the whole world. This is D.

Viewed in this way, the prophecy of Daniel is the story of the wars of the nations against Jesus Christ – and finally the victory of Messiah the Prince over the kingdoms of this world through the salvation of His people. The Book of Daniel is like a pair of books – the first prophetic-historical and the second prophetic – or a single book that hinges in the middle. At the outer pairing in the first chiasm is the prophecy of Messiah’s kingdom. At the center of the second chiasm is the “seventy weeks” prophecy that gives the exact timing of the coming of Messiah’s kingdom. Both the first and second chiasm must be interpreted consistently to show that Christ’s victorious kingdom would come – “In the days of these kings” (Daniel 2:44) – in the days of the Roman Empire.

One of the two supposed difficulties with the prophecy of Daniel is that it is one of only two books in the entire Bible composed in two different languages. (The other book being Ezra, in which the several letters contained in the book were originally composed in Aramaic and not deemed necessary to be translated into Hebrew.) Daniel chapters 1 and 8-12 are written in Hebrew like the rest of the Old Testament. But Daniel chapter 2 dramatically and abruptly shifts into Chaldean Aramaic, which was the language spoken by the Babylonians.

The second alleged difficulty is that the first half of Daniel, chapters 1-7, is written in the third person. Then in chapters 8-12, Daniel begins to refer to himself in the first person, “I.” This begs a number of questions.

Do these shifts imply two authors or one?

Why two languages?

Why the shift in point of view?

It is best to apply the proverbial “Occam’s razor” here. All things being equal, the simplest explanation is the best one.

The Chaldean portions were composed as a narrative record when Daniel was made ruler over the whole province of Babylon, the chief of the governors over all the wise men of Babylon (2:48), later “the third ruler in the kingdom” (5:29) and finally a well-respected and prosperous man during “the reign of Darius, and in the reign of Cyrus the Persian” (6:28).

This was a piece of Chaldean literature meant for a Babylonian-Chaldean and Jewish audience, Babylon being the capital city and the Chaldea being the region. This portion was originally composed in Chaldean Aramaic, which became the lingua franca of the Jewish world after the Babylonian captivity. It was not deemed necessary to translate these portions into Hebrew. Furthermore, recent analysis has shown that the Chaldean of Daniel is “Official Chaldean” of that era and not the “Western Aramaic” dialect spoken at the time of the Maccabean revolt in the 2nd century BC and later.

Daniel 1 begins in Hebrew in the third person point of view. Then Daniel 2:4 abruptly shifts to another language.

The Chaldeans spoke to the king in Aramaic: “O king, live forever! Tell the dream to your servants, and we will declare the interpretation.”

This sudden shift from Hebrew to “Chaldee” or “Chaldean Aramaic” can be likened to the dialog in a modern movie that takes place in a foreign country, such as Russia or Germany. For realism sake, the script writers begin with the foreign language and the film provides subtitles. But at a certain point the film shifts to English to make the viewing experience easier for the movie goer. Although this may seem like a trite analogy, the “story-teller” aspect of the historical narrative is meant to captivate the reader. Read aloud, the dramatic shift into Chaldee would lend a sense of realism and immanence for contemporary Jewish audiences.

Since nearly all Jews after the restoration period spoke both Chaldean Aramaic and Hebrew, the first chapter of Daniel, which contains the story of the prophet, is told in Hebrew to establish the point of view of Daniel/Belteshazzar as a young captive among King Nebuchadnezzar’s royal prisoners from Jerusalem. Then the narrative shifts to the common tongue of the Post-Exile era Jews, Chaldean Aramaic. Then when the book shifts to the prophecies concerning the later kingdoms – Medo-Persia, Macedonia-Greece and Rome – the prophet uses Hebrew, which was the language of all other prophetic books possessing the authority of Scripture.

The famous “handwriting on the wall” episode during Belshazzar’s feast in Daniel 5 has caused many to wonder why Daniel could read, “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin,” while the court’s most learned magicians could not. The simplest explanation is that these common words, when written Hebrew and Aramaic, looked very different even though they were pronounced similarly. Early Hebrew script, sometimes called the angular script, was used prior to the Babylonian exile in 586 BC. After the exile, the Aramaic script of the Chaldean period, sometimes called the square script, was adopted for the Hebrew language. The square script is still used today (cf. Craig Davis, Dating the Old Testament, p. 368).

Daniel’s language from his youth prior to the captivity was Hebrew. He would have kept that language and the Early Hebrew script close to his heart. As a young Hebrew nobleman, he would have been expected to know the Hebrew Scriptures and be able to read and write. The handwriting on the wall looked one way in Hebrew, but read out loud the words sounded like Chaldean Aramaic and suggested a play on words.

Mene – Literally a mina (50 shekels) comes from the verb “to number” and literally a shekel comes from the verb “to weigh.”

Tekel – Literally and half-shekels comes from the verb “to divide.”

Upharsin – The Aramaic Paras is cognate with Peres, and sounds like the word for “Persian.”

“This is the interpretation of each word. MENE: God has numbered your kingdom, and finished it; TEKEL: You have been weighed in the balances, and found wanting; PERES: Your kingdom has been divided, and given to the Medes and Persians” (Daniel 5:25-29).

Using two languages throughout the book underscores the overthrow of the Babylonian Empire. During this famous event in ancient history recorded by Herodotus, the Medes and Persians built a dam on the river Euphrates that flowed through the city of Babylon watering its beautiful gardens. The lower water level enabled them to wade through city gates and take the city in one day, literally establishing a new Medo-Persian Empire overnight.

Daniel 8-12 then shifts to Hebrew because it is intended to be a predictive prophecy for a later time. Daniel here speaks with the authority of a prophet in the first person in the style of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and all of the Minor Prophets (with the exception of the Book of Jonah, which is told in the third person except for the actual prophecy itself and the prayer portions). The Book of Daniel has a similar structure as the Book of Jeremiah, in which the historical portions are told in the third person, but Jeremiah’s prophecies are told in the first person.

your_ip_is_blacklisted_by sbl.spamhaus.org