America is the only nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in the Declaration of Independence; perhaps the only piece of practical politics that is also theoretical politics and also great literature. It enunciates that all men are equal in their claim to justice, that governments exist to give them that justice, and that their authority is for that reason just. It certainly does condemn anarchism, and it does also by inference condemn atheism, since it clearly names the Creator as the ultimate authority from whom these equal rights are derived. Nobody expects a modern political system to proceed logically in the application of such dogmas, and in the matter of God and Government it is naturally God whose claim is taken more lightly. The point is that there is a creed, if not about divine, at least about human things.

― G.K. Chesterton, British historian and philosopher, “What I Saw in America”

The United States of America owes its existence to several centuries of political philosophy, which began shortly after the Protestant Reformation and the overthrow of the doctrine of the “Divine Right of Kings.” At the time of the American Revolution, the colonists realized that the protection of liberty could only be accomplished practically through armed resistance. A few years later, the framers of the Constitution asserted the right of the states to interposition and nullification when the federal government overstepped its own authority.

While it is generally accepted that under our Constitution, the states are not guaranteed a “right to secession” whenever they desire to defy federal mandates, there is a long history of the states using the doctrine of nullification. That is, they may resist federal legislation when those laws are not consistent with the powers of the federal government enumerated in the Constitution. Recently, we have seen a number of states pass various Tenth Amendment resolutions. We have also seen a number of recent state laws that are designed to resist the imposition of the federal Affordable Health Care Act (ObamaCare). To determine whether this is a legally valid approach, we need look no further than our own history as a model for resistance and nullification.

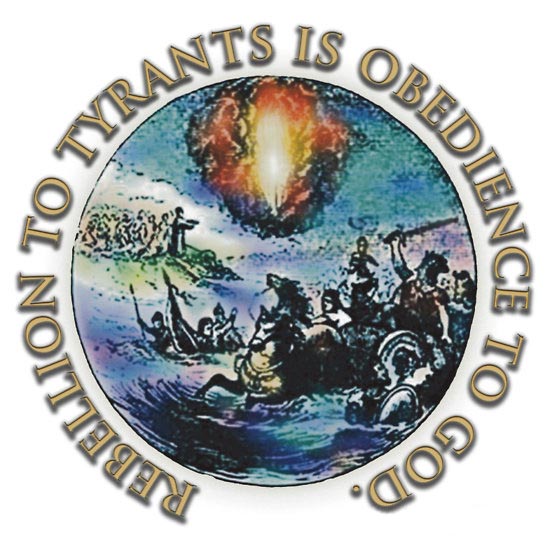

Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God

In 1776, a short time after the Declaration of Independence was adopted, the same committee who were assigned to draft the text of the Declaration – Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin – were also assigned to design an official seal for the United States of America. Benjamin Franklin’s proposal is preserved in a note in his own handwriting:

Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity. “Motto, Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God” (First Committee’s Design for the Great Seal).

John Adams later described Jefferson depiction of the Great Seal:

Mr. Jefferson proposed: The children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a pillar of cloud by day, and a pillar of fire by night, and on the other side Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs, from whom we claim the honour of being descended and whose political principles and form of government we have assumed.

When we peruse history textbooks used by public school students little more than 100 years ago, we see a long tradition in American education of portraying our founding fathers as Godly men, George Washington being the chief “Christian hero” among them. Modern skeptics, on the other hand, like to characterize our founders as Enlightenment Deists and perhaps even infidels. To be completely objective, we have to admit that there was not a single church denomination or religious philosophy that led the way. There is no question that our Founding Fathers were an amalgamation of some Deistic humanists, who had little use for religion in their private lives, as well some Congregationalists from New England who still held to Puritan thought, together with Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists, Roman Catholics and Quakers, all jostling for position in the context of our founding federal documents.

A brief survey of the church membership of the founders shows that at least 50 of the 55 signers of our founding documents were orthodox Christians – and the vast majority were members of churches that held to either the Westminster Confession, the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England or some other historic Reformed Confession of Faith. Even among the small minority who held to no church creed or confession – Franklin and Jefferson being among them – there was an acknowledgment of man’s overriding depravity and the idea that absolute power corrupts absolutely. The Declaration of Independence itself carries the following phrases expounding on the Christian idea of God.

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the Powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions …

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

These names of God do not indicate a philosophy of Deism, but taken together, must refer to the God of the Bible – Jesus Christ – who will ultimately punish evil doers and reward covenant keepers. The names of God in the Declaration of Independence correspond to the attributes of a God who is active in the events of history.

- Nature’s God – “For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse” (Romans 1:20).

- Creator – “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…. So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them (Genesis 1:1,27).

- Supreme Judge – “To the general assembly and church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, and to God the Judge of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect” (Hebrews 12:23).

- Divine Providence – “That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45).

Taken separately, any of these titles must refer to a monotheistic God, but may also include a Deistic conception. However, taken together, all of these titles of God must refer to the Christian God. Only the God of the Bible is the Ruler of all nature, our Creator, Judge and Provider.

“We have this day restored the Sovereign …”

To make it clear which God the founders were appealing to when the Declaration was being signed, Samuel Adams said: “We have this day restored the Sovereign to Whom all men ought to be obedient. He reigns in heaven, and from the rising to the setting of the sun, let his kingdom come” (alluding to Isaiah 45:6).

Although our founders went to great lengths in appealing to natural law philosophy to justify a long war with one of the world’s superpowers, Great Britain, the men who had the audacity to rally the colonies to war believed that if God himself had favored their efforts, they would be successful.

Patrick Henry’s well-known “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death!” speech to the Virginia Convention, delivered on March 23, 1775, at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, includes the fabled lines:

Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us. Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations; and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.

Meanwhile in colonial Massachusetts, the call to arms was not the accomplishment of the later president, the even-tempered Unitarian John Adams, but that of his Calvinist firebrand second cousin Samuel Adams. The various Christian denominations were by no means united in this call. Many of the Quakers at the time opposed the War for Independence from Great Britain. They issued a paper in opposition to the war entitled: “To the People in General.” The Quakers protested that “the setting up, and putting down kings and governments, is God’s peculiar prerogative; for causes best known to himself: and that it is not our business, to have any hand or contrivance therein; nor to be busybodies above our station, much less to plot and contrive the ruin, or overturn of any of them.” But more importantly, they encouraged others not to fight either. Samuel Adams, the architect of the American Revolution, issued the counterpoint, “To the People in General,” and signed himself, “A Religious Politician.”

He who sets up and pulls down, confines or extends empires at his pleasure, generally, if not always, carries on his great work with instruments apparently unfit for the great purpose, but which in his hands are always effectual…. God does the work, but not without instruments, and they who are employed are denominated his servants; no king, nor kingdom was ever destroyed by a miracle, which effectually excluded the agency of second causes…. We may affect humility in refusing to be made the instruments of Divine vengeance, but the good servant will execute the will of his master. Samuel will slay Agag; Moses, Aaron, and Hur, will pray in the mountain, and Joshua will defeat the Canaanites (Giddings, Rev. Edward J. American Christian Rulers. New York: Bromfield & Company, 1889. p 4).

The Christian Idea of Man and Government

The above quotes show that a Christian idea of man and government was in the minds of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. They understood that their endeavor would be successful because it was ordained of God. Further, the theology of the Protestant Reformation was at the forefront of the founders’ thinking. The Declaration of Independence was the culmination of a thought process begun by men such as Samuel Rutherford, the Scottish Presbyterian theologian, who wrote Lex Rex in 1644 to refute the idea of the divine right of kings.

Lex Rex established two essential principles for civil government. First, there should be a covenant or constitution between the civil ruler and the people that would be binding in the sight of God. Second, since all men are sinners, absolute power corrupts absolutely. Therefore, corresponding checks and balances must be in place to protect the God-given rights of the people against civil tyranny.

Lex Rex is a also profound play on words. Prior to Rutherford, the supporters of King Charles I had maintained that “the king is the law” or Rex, Lex. Rutherford maintained that “the Law is king” or Lex, Rex. The Law that Rutherford had in mind was God’s Law. Therefore Christ, not man, is king. We are to be ruled by a system of civil government under God’s Law, not man. This is a uniquely Christian concept derived from a covenantal interpretation of the Bible.

While Deists such as Thomas Paine stressed that correct moral and ethical principles could be understood from a natural law viewpoint, in the end the will to act on these principles was a great leap of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. The God of the American founders was not a distant Deity who had merely wound up a clockwork universe guided by natural law. No, this God was present in the everyday affairs of human beings – the King of kings.

By the 1770s, a number of the Founding Fathers were also influenced by Enlightenment ideas that ultimately came to be known as Deism or Unitarianism. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were examples of these men. Both had been celebrated in Enlightenment France as “free thinkers.” Both were later sent there as ambassadors where they absorbed both the social philosophy and the loose morality of the French court. They demonstrated the fruit of their free thought in their profligate private lives. But in their public demeanor in America they were inconsistent. Benjamin Franklin was best known in the Constitutional Convention for calling for prayer that divine providence would guide all the proceedings of that great assembly. Thomas Jefferson read the Bible every day, even if he only read portions of it and disbelieved in the miraculous. (Grant, George. God’s Law and Society).

Our founding documents did not come primarily as summary of the writings of the French Enlightenment social philosophers, although there are large areas of agreement between these viewpoints and those of the prior Christian reformers.

- Montesquieu’s (1699-1715) view that human beings are selfish influenced the founder’s insistence that the checks and balances are needed.

- Jean Jacques Rousseau’s (1712-1778) “social contract theory” also certainly had an important contributing influence, but it had been a well-accepted doctrine expounded upon by John Calvin, Samuel Rutherford and others.

- John Locke (1632-1704) stripped “social contract theory” from its theological nomenclature in order to make it more palatable to Enlightenment thinkers.

These are ideas that sprang from the recovery of a biblical view of man and government at the time of the Reformation and especially among the writings of the English and American Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians. In fact, almost every line found in our founding documents was cobbled together from dozens of previous colonial charters, constitutions and even political sermons delivered from Puritan pulpits that had circulated in America since the early 1600s.

The American Experiment

The American experiment with constitutional government devised by the Puritan colonies became the model for the United States Constitution. For example, the Puritan minister Thomas Hooker helped found a new colony at Hartford and assisted in the drafting and adoption of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut in 1639. Harvard historian John Fiske writes:

It was the first written constitution known to history, that created a government, and it marked the beginnings of the American republic, of which Thomas Hooker deserves more than any other man to be called the father. The government of the United States today is in lineal descent more nearly related to that of Connecticut than to that of any of the other thirteen colonies. The most noteworthy feature of the Connecticut republic was that it was a federation of independent towns, and that all attributes of sovereignty not expressly granted to the General Court remained, as of original right, in the towns (Fiske, John. Beginnings of New England, or the Puritan Theocracy in Its Relation to Civil and Religious Liberty. Houghton Mifflin Company, the Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1889. pp. 127–28).

The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut is one example of a biblical covenant with God, which also served as a basis for civil government. This document states that Connecticut was submitted to the “Savior and Lord.” Connecticut began as a true federal union under God, the first since the days of the Hebrew Commonwealth.

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), compiled by the Puritan minister Nathanel Ward, was a document that contained individual rights explicitly cited as originating from biblical sources and later became the model for America’s Bill of Rights.

Jonathan Mayhew’s sermon, Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-resistance to the Higher Powers: with Some Reflections on the Resistance Made to King Charles I (1750) became the inspiration for the Declaration of Independence. In fact, John Adams considered Mayhew’s sermon the spark that ignited the Revolution.

Another gentleman who had great influence in the commencement of the Revolution was Dr. Jonathan Mayhew, a descendant of the ancient governor of Martha’s Vineyard. This divine had raised a great reputation both in Europe and America by the publication of a volume of seven sermons in the reign of King George II, 1749, and by many other writings, particularly a sermon in 1750 on January 30, on the subject of passive obedience and nonresistance, in which the saintship and martyrdom of King Charles I are considered, seasoned with wit and satire superior to any in Swift or Franklin. It was read by everybody, celebrated by friends, and abused by enemies.

During the reigns of King George I and King George II, the reigns of the Stuarts (the two Jameses and the two Charleses) were in general disgrace in England. In America they had always been held in abhorrence. The persecutions and cruelties suffered by their ancestors under those reigns had been transmitted by history and tradition, and Mayhew seemed to be raised up to revive all their animosity against tyranny in church and state, and at the same time to destroy their bigotry, fanaticism, and inconsistency. David Hume’s plausible, elegant, fascinating, and fallacious apology, in which he varnished over the crimes of the Stuarts, had not then appeared. To draw the character of Mayhew would be to transcribe a dozen volumes. This transcendent genius threw all the weight of his great fame into the scale of his country in 1761, and maintained it there with zeal and ardor till his death in 1766 (Niles’ Weekly Register, March 7, 1818).

“Christ, not man, is king.” – Oliver Cromwell

It might come as a surprise to some today to realize that our second president considered the Battles of Lexington and Concord to have been fomented out of the same ideology that drove the English Civil War a century earlier – to the Puritan battle cry that is inscribed as the epitaph on Oliver Cromwell’s tomb in Westminster Abbey, “Christ, not man, is king.”

Just a few years later, the Preamble to the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights (1780) made it clear that the state was under the authority and rule of God.

We, therefore, the people of Massachusetts, acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the goodness of the Great Legislator of the Universe, in affording us, in the course of His providence, an opportunity, deliberately and peaceably, without fraud, violence or surprise, of entering into an original, explicit, and solemn compact with each other; and of forming a new Constitution of Civil Government, for ourselves and posterity, and devoutly imploring His direction in so interesting a design, Do agree upon, ordain and establish, the following Declaration of Rights, and Frame of Government, as the Constitution of Massachusetts.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783, negotiated by Ben Franklin and John Adams among others, is a foundational document for the United States, because by this Treaty England recognized American independence. It begins with these words:

In the Name of the most holy and undivided Trinity….

The United States Constitution, although it differs from the colonial charters’ references to the Christian faith, was secular in appearance only. In fact, its primary purpose was to ensure the rights of the people through local government. The First Amendment was intended to protect the states from interference by the federal government.

The First Amendment prohibited laws respecting the establishment of religion because religion was already established at the local level. In fact, at the state level, there were Sabbath laws, religious tests for citizenship, suffrage and office holding. There were civil codes criminalizing adultery, sodomy and blasphemy — all of them connected to biblical law and even quoting scripture. In this view, the Constitution did not need to include an explicit reference to the “Creator,” “Jesus Christ” or the “Trinity” simply because each state already had an establishment of the Christian religion if not a denominational requirement.

Likewise, the criticism that the U.S. Constitution failed to recognize biblical law by substituting John Locke’s philosophy of natural law fails simply because Constitutional Law was understood in the context of various Christian commonwealths from which the federal government derived its power.

First, the idea of natural law is derived from scripture itself. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution assumes that our God-given rights are self-evident; that is, even people without the Bible can see them (Romans 1:18-20). These rights are life, liberty and property. These rights exist even without civil government. The natural limit of government is to protect these rights. However, only those people who are able to be self-governing under God’s laws found in the Bible are capable of enjoying the full privileges of these rights.

Second, the Constitution of the United States assumes that the American people are fully capable of being self-governing. Thus the Constitution affirms both the natural law and the Biblical law as the basis of a moral code that every citizen is bound to obey. The sole purpose of the Constitution is to “secure the blessings of liberty” which a God-fearing people ought to enjoy. Thomas Jefferson himself wrote that natural rights were also moral duties.

Man has been subjected by his Creator to the moral law, of which his feelings, or conscience as it is sometimes called, are the evidence with which his Creator has furnished him…. The moral duties which exist between individual and individual accompany them into a state of society … their Maker not having released them from those duties on their forming themselves into a nation (Opinion on French Treaties, 1793. Memorial Edition 3:228).

Reading such pious words in our founders’ writing, it is easy for Christians today to despair at the heights from which we have fallen as a nation. We have arrived at such a low point that even now the right to display a nativity scene on a courthouse lawn is commonly challenged by the ACLU and the American Atheists organization. Unfortunately, our conservative media outlets and Christian legal defense groups tend to focus on these hot-button news items, while failing to see the underlying cancer that lies at the root of these symptoms.

1 Comment

VERY good Jay!!